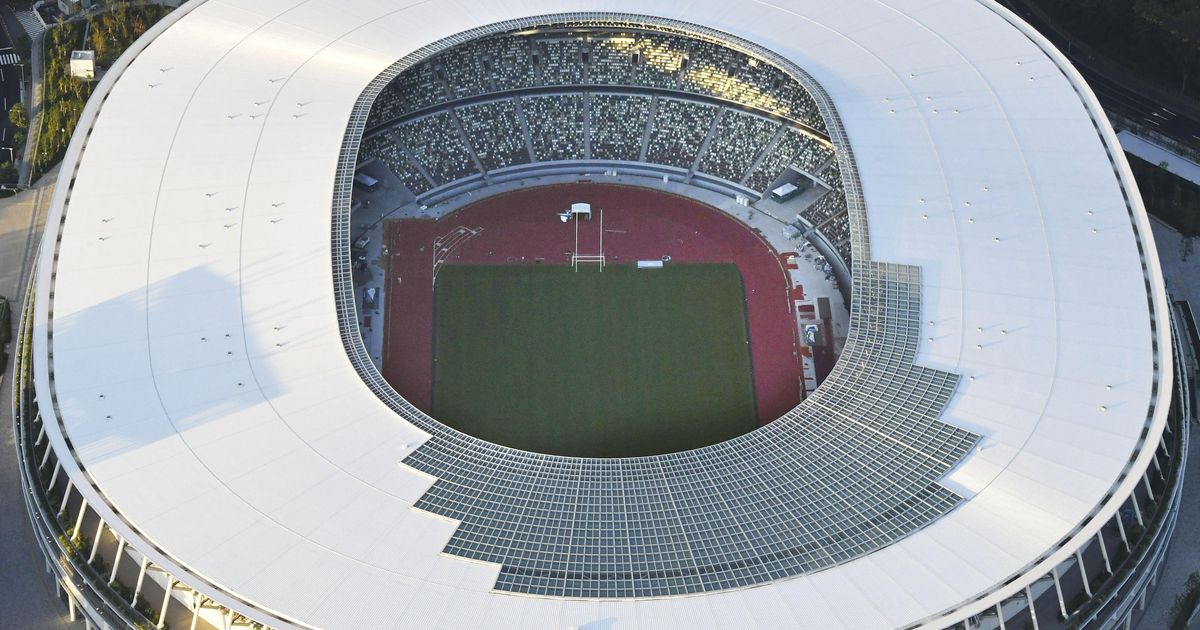

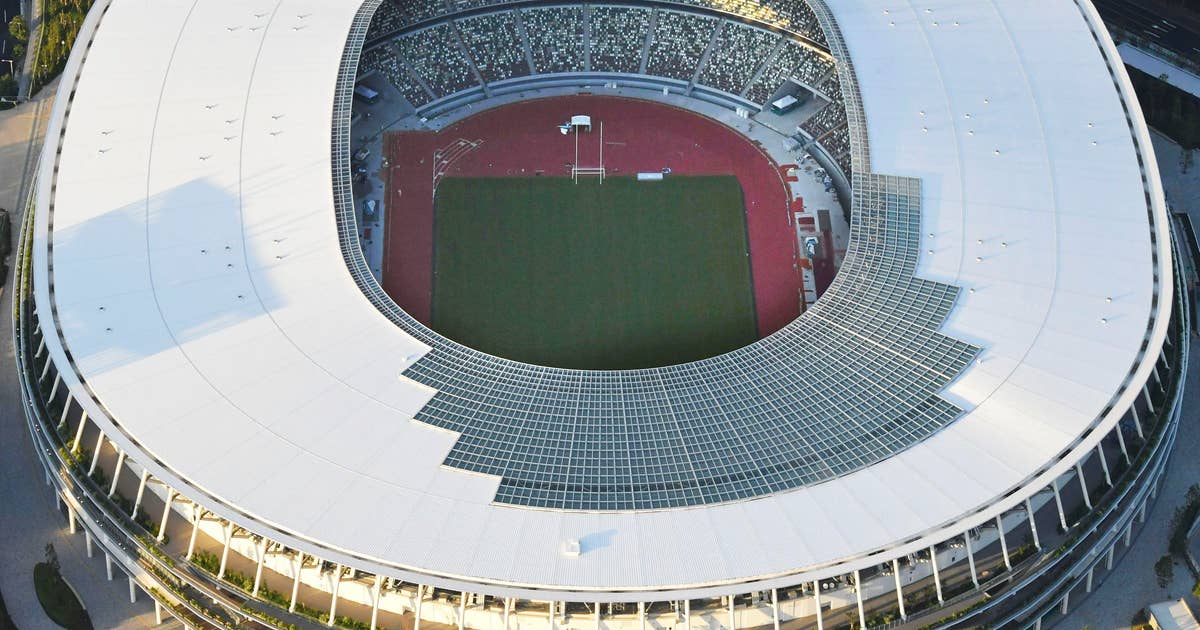

Tokyo Games: Union wants venue inspection, worker interviews

TOKYO (AP) — An international labor union investigating worker safety and the use of migrant workers at venues for next year’s Tokyo Olympics is asking for a joint inspection of construction sites and an open interview with workers.

The Building and Wood Workers’ International, in a report earlier this year titled “The Dark Side of the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics,” alleged patterns of overwork and contract irregularities at Tokyo venues with attention focused on foreign workers.

In an interview in Tokyo, BWI General Secretary Ambet Yuson said he will request a “construction audit or a joint inspection” in a meeting Thursday with officials of the local organizing committee, the Japan Sport Council and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

“They are overprotective and don’t want the outside to come in,” Yuson told The Associated Press. “They are trying to downplay it, saying construction is almost over. But it’s not over until the Olympics are over. Construction is dangerous and every worker you save makes a difference.”

The Japan Sport Council — a national government body — is building the $1.25 billion national stadium, and the Olympic Village is being built by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

Yuson said BWI, based in Switzerland, has interviewed 50 workers in Tokyo to gain a picture of labor practices at Olympic venues. He said the union was not granted access to the workers, and many who spoke fear they may lose their jobs if their names are revealed.

He said the majority are Japanese with a mix of Vietnamese, Chinese and Filipinos.

“If they don’t believe me, they can listen to these workers,” Yuson said.

Death by overwork, known as “karoshi,” is a problem in Japan where long working hours are common. Yuson also noted that many construction sites have signs about health and safety written only in Japanese, unhelpful for foreign workers.

Yuson said 300 workers — Japanese and non-Japanese — die annually on construction work in Japan.

Japan’s labor ministry, in a report issued 10 months ago, said two workers have died on projects for the Tokyo Olympics.

Yuson said he has asked the International Olympic Committee to step in, perhaps using leverage on the Tokyo organizing committee.

“The IOC doesn’t push,” he said.

Many sports governing bodies have signed up the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which spell out practices for businesses and government. They include soccer governing bodies FIFA and UEFA, the Commonwealth Games Federation, the International Paralympic Committee and Qatar’s 2022 World Cup.

The IOC has added the UN guidelines to host city contracts that come into effect with the 2024 Paris Olympics. That excludes Tokyo, and the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing, where independent labor unions are barred by China’s authoritarian government.

Yuson said Tokyo conditions have improved some since the report was issued earlier this year. But he said continued research had uncovered added problems linked to worker safety and overtime.

“We want to bring legacy to the Olympics, not only to the multinational companies, or to the athletes, but to the workers as well,” Yuson said.

A report released last year by the national government’s Board of Audit said Japan is likely to spend $25 billion overall to prepare for the games. This is public money, except for the $5.6 billion operating budget.

Organizers dispute the figure and say it’s about $12 billion, though what are Olympic costs — and what are not — is subject to heated debate.

Tokyo projected total costs of about $7.5 billion in its winning bid for the games in 2013.