IOC, WADA hire DC lobbyists to discuss anti-doping bill

KATOWICE, Poland (AP) — Not long after a bill that would criminalize international doping conspiracies advanced in the U.S. Congress, world Olympic and anti-doping leaders made clear how they felt about the development.

They started lobbying for changes in Washington.

The International Olympic Committee and World Anti-Doping Agency have each devoted six-figure budgets to get word out on their issues with the Rodchenkov Act.

The bill, named after the Moscow lab director who blew the whistle on Russia’s plan to cheat at the Sochi Olympics, passed the U.S. House last month and is now awaiting action in the Senate.

The measure calls for fines of up to $1 million and prison sentences of up to 10 years for those who participate in schemes designed to influence international sports competitions through doping. It would also allow the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency to obtain information collected by federal investigators, which could help prosecute anti-doping cases.

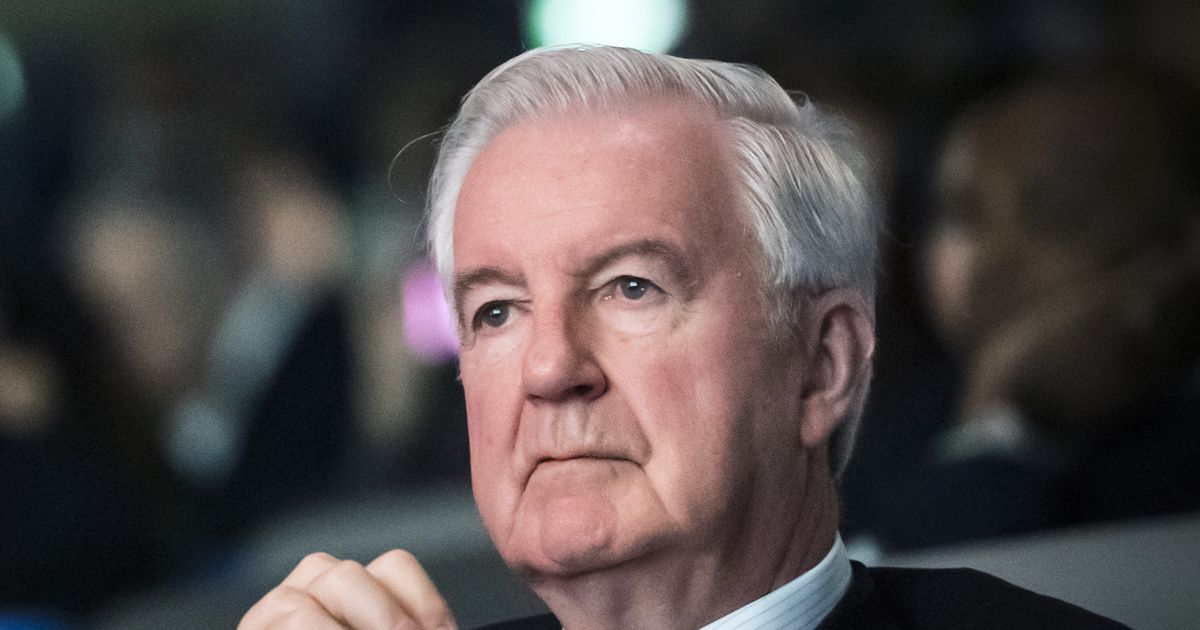

WADA President Craig Reedie said the agency favored the part of the bill that calls for transferring information.

“The area which is troublesome is the suggestion that American jurisdiction would go beyond the United States and might create liability in other parts of the world,” he said.

WADA documents obtained by The Associated Press say the agency has budgeted “at least” $250,000 to continue the lobbying effort into next year.

As the bill is currently written, a company such as Nike could run afoul of the law for its connection to Alberto Salazar, the famed track coach who recently received a four-year ban for violating the anti-doping code. Or it would have made it easier to prosecute people involved in the FIFA soccer-bid scandal, many of whom were charged in the U.S. under fraud, racketeering and money laundering laws.

The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee and U.S. Anti-Doping Agency are among the backers of the bill, which originally included language that allowed for individual prosecution of athletes that was later stripped. That language, some critics felt, could’ve discouraged foreign athletes from competing in the United States.

Rodchenkov’s lawyer, Jim Walden, said the IOC’s position on the law proves they “would rather host dirty games than have anyone else police doping fraud.”

“If the IOC and WADA want to lobby U.S. lawmakers on behalf of Russia’s corrupt interests, that is a serious problem and I would encourage our congressmen and senators to be very wary of these efforts,” he said.

Rob Koehler of the athlete’s group Global Athlete said he was similarly surprised, “given the bill’s ability to eradicate the people who are enabling doping.”

The IOC said it was appreciative of efforts to control doping in the United States.

“However, it is a matter of concern that the intention of the proposed legislation is to put athletes from all 206 National Olympic Committee from around the world who take part in international competition under the criminal code of U.S. law,” said a statement provided to the AP by an IOC spokesman.

Travis Tygart, the CEO of the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency, dismissed that idea, saying the possibility of prosecuting individual athletes was taken out of the bill.

It will soon become clear how effective the lobbying efforts are.

The bill, especially after it was revised, has gained wide support. It passed on a voice vote, without opposition, in the House. It has bipartisan support in the Senate.

And in a sign of how seriously it takes the issue, the White House has assigned a political appointee, Kendel Ehrlich, to the government’s anti-doping team. In October, the Office of National Drug Control Policy hosted a first-of-its-kind summit to discuss doping in sports.