NFL Hall of Famers seek pension parity for old-timers

SAN FRANCISCO (AP) — As the NFL gears up for a yearlong celebration of its history for its 100th season, some of the stars who helped build the league into the behemoth it has become want to make sure the old-timers are no longer left behind.

For the last quarter-century, the league has had a two-tiered system when it came to pensions, paying out significantly bigger amounts to more recent retirees than the players who retired before 1993 and made considerably less money in the pre-free agency days.

If that discrepancy is going to be eliminated, those old-timers know time is running short.

“It’s something that’s been talked about for the last 20 years,” Hall of Fame running back Franco Harris said. “It’s just been talk. And no one’s walked the walk yet. We have to make sure that this is just not talk this time. So when people say certain things and then they say certain things up to the time, and then it doesn’t happen, it passes by and people tend to take it off the radar. But we can’t take it off our radar now. So it’s important that people know that. We’ll focus on this. We’re not going to let it go.”

Harris is one of several high-profile former players who are part of a nonprofit group called Fairness for Athletes in Retirement that is fighting to get players who retired before 1993 the same level of pensions as more recent players after years of fruitless attempts at parity.

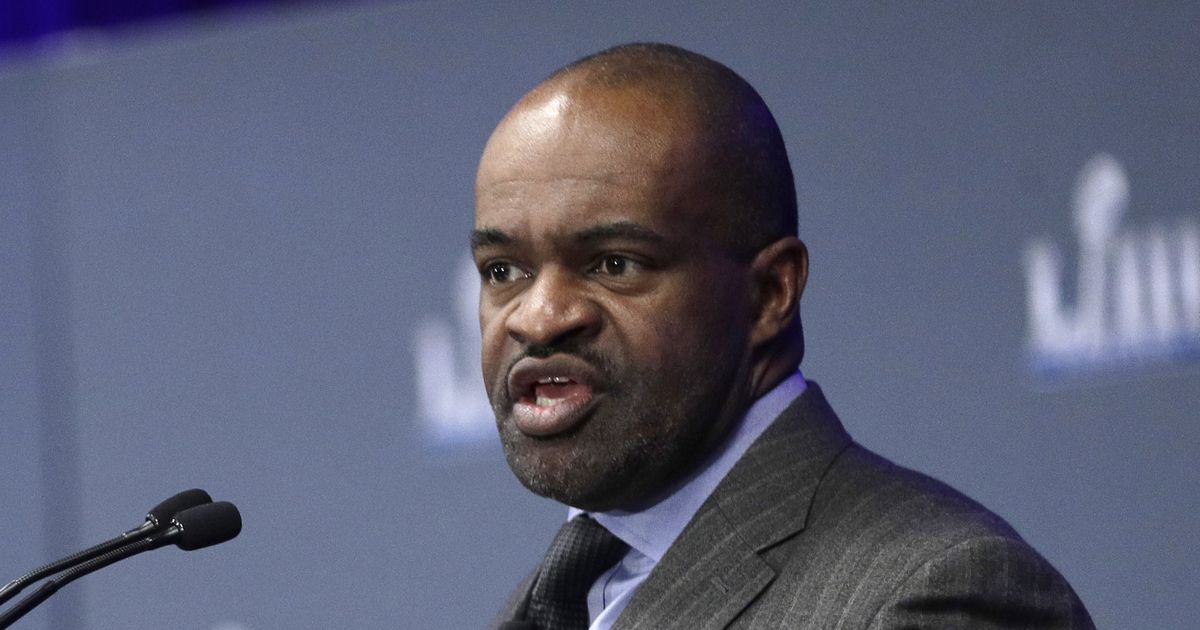

The group was encouraged by comments made by NFLPA executive director DeMaurice Smith at his annual pre-Super Bowl news conference, saying improved pensions would be a priority in upcoming labor negotiations.

“We have always reached back and improved pensions,” Smith said. “I think it’s smart that former players understand that we can accomplish more in improving benefits. This is a union that is never going to select a certain group of players over another group of players.”

But they are waiting to see results when the union and the league negotiate the next collective bargaining agreement following the 2020 season.

According to FAIR, players who played before 1993 get about $3,000 for every year played, while current players get a pension benefit worth about three times that amount.

The old-timers have gotten only one pension increase in the past 38 years through the “legacy benefits” in the last accord in 2011 that supplemented the pensions for old-timers by between $108 and $124 monthly per credited season.

More recent retirees also get medical benefits, life insurance, a 401(k), and an annuity. But the old-timers aren’t seeking any of those benefits, focusing solely on getting their pensions on equal footing with the modern players.

“Everything is off the table except the pensions,” Hall of Fame guard Tom Mack said. “There are so many other things that the younger guys have, but we’re just saying we need the pensions so guys can make the decisions they can for themselves.”

There are approximately 3,800 players who retired before 1993 currently receiving pensions and FAIR estimates it would cost each team between $5 and $6 million a year, as well as a similar amount from the players through a reduced salary cap of less than 3 percent to achieve equity with current players.

With an average of more than 100 of the old-time players dying each year, only a fraction of those players will still be remaining if the sides do another 10-year deal without reaching pension parity.

“Most of us will be dead by then,” 67-year-old Hall of Fame tight end Dave Casper said of the possibility of another decade-long deal without addressing the issue. “It’s going to go away. This little bunch of us will be gone. I personally don’t want anyone playing today to think that we think that they’re bad guys. I don’t think that they really know. I don’t think they think about it. If this is an opportunity for anything, it’s that they now have the opportunity to take a look at it.”

While the other major North American sports leagues also pay different amounts in pensions based on when players retired, the old-time NFL players lag significantly behind their contemporaries in other sports — despite having more health problems in old age based on the physical nature of football.

FAIR said a Major League Baseball player who retired after 1980 following a 10-year career receives about $200,000 yearly at age 62, and the NBA union said a 10-year veteran who retired after 1965 receives about $225,000 a year at age 50.

The pre-1993 retirees have tried different approaches over the years to improve their pensions, including highlighting the most dire cases through the wives of struggling retirees.

Now it’s a group of Hall of Famers trying to raise awareness so the public, and perhaps more importantly the current players, are aware of the plight and will prioritize pension parity in labor negotiations.

“A lot of us here in this room will be probably still OK if we don’t get the pension,” Casper said. “But there’s a lot of guys out there that can’t even afford to come here. They can’t get on a plane and advocate so we’re advocating for them.”