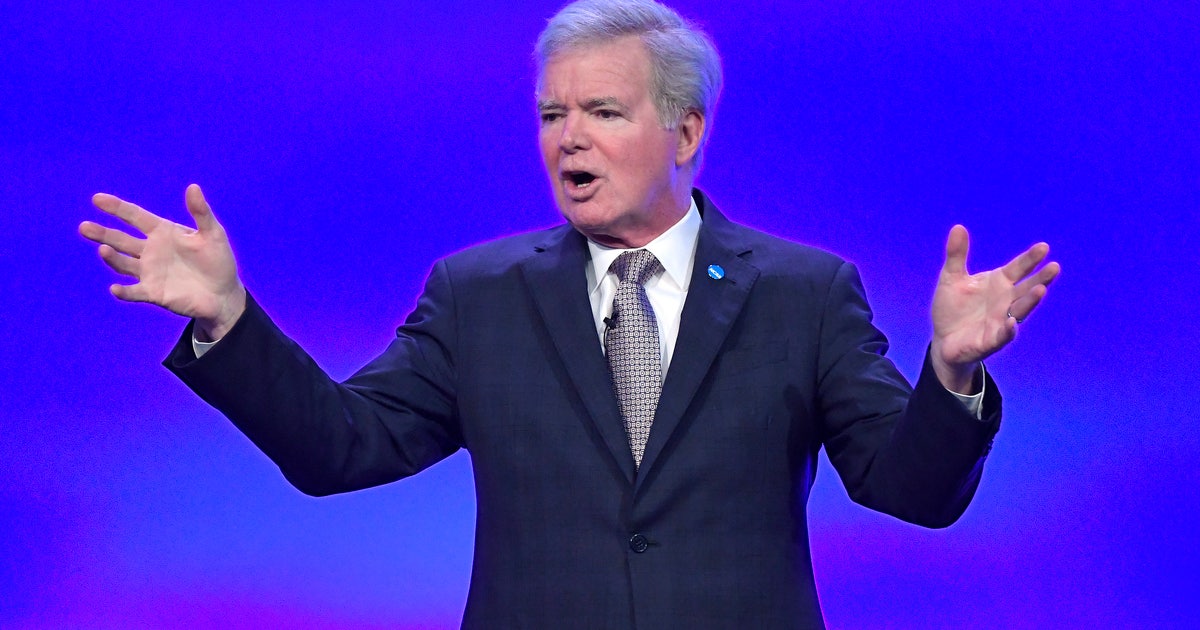

NCAA’s Emmert: ‘Our job’ to solve athlete compensation

ANAHEIM, Calif. (AP) — NCAA President Mark Emmert spoke for 20 minutes Thursday in a crowded ballroom at the Anaheim Convention Center, two huge video boards on either side of the stage showing his image so the folks way in the back could see.

He said many outside that room view college sports as fundamentally unfair to the athletes. He said the public and political pressure the NCAA is facing as its leaders try to find a way to allow athletes to make money off their fame is a symptom of that larger problem. As big-time college sports has become a multibillion dollar business, the public’s trust in the NCAA to do the right thing for athletes has waned, Emmert said.

“Yes, in some cases, we need help from Congress and from some others,” Emmert said. “But this is our job and we got to be clear about it. This is ours to improve and make better.”

Regarding the immediate issue of permitting athletes to be compensated for their names, images and likenesses, this convention was more about talking through solutions than producing one.

“Right now, everything’s on the table,” said Ohio State athletic director Gene Smith, who is leading a group of athletic administrators charged with crafting new rules. “You’re early in the process.”

The short-term goal is to have recommendations for the NCAA Board of Governors in April that can lay the groundwork for legislation to be voted on next January. All of that could be trumped by what happens in Washington when federal lawmakers step into the business of regulating college sports.

“People in Washington want to know what the desires are of college sports and we need to work with them to help them figure that out,” Emmert told reporters after his speech.

Grace Calhoun, University of Pennsylvania athletic director and the chairwoman of the NCAA’s Division I, said small groups of athletic administrators are examining three areas where athletes could earn money.

— Student-athlete work product, which covers things such as starting a small business, earning money for writing a book or charging for lessons in their sport. This is likely the easiest area to ease restrictions because currently the NCAA is granting a high percentage of waiver requests to permit these activities.

— Individual licensing , which covers endorsement and sponsorship deals with a single athlete.

— Group licensing in which athletes could earn a percentage of profits from something like the old NCAA Football video game. The game was discontinued in 2014 when the NCAA was facing a federal antitrust lawsuit for improperly using athletes names, images and likenesses.

Calhoun said group licensing presents the most challenging questions.

“At the end of the day, we’re dealing with student-athletes and when we look at our principals, we’ve established we won’t cross that line from them being students to turning into employees,” she said Wednesday. “So when you start looking at a group acting together, keeping the line as a student becomes a little more complex.”

This week NCAA officials — at least publicly — rehashed talking points that have been making the rounds since late October when the board voted to allow college athletes to profit from their fame.

That came a month after California passed a law that would make it illegal for NCAA schools to prohibit college athletes from making money on endorsements, autograph signings and social media advertising, among other activities. The California law intends to permit college athletes to enter the free market with few restrictions.

Dozens of states have followed California’s lead. Some more aggressively than others. California’s law does not go into effect until 2023. Lawmakers in eight other states, such as Florida and Pennsylvania, have said they would like to have laws in place later this year.

Facing the possibility of a patchwork of state laws creating different standards for competing schools, NCAA leaders have turned to federal lawmakers for help.

Senators Chris Murphy (D-Conn.) and Mitt Romney (R-Utah) have established a working group to examine issues in college sports. Emmert met with them in December. Smith said it is imperative for officials at every school to be communicating with lawmakers in their states.

Meanwhile, a group of university presidents is communicating with Congress and members of the senate on the NIL issue. The NCAA’s presidential subcommittee of the federal and state legislation working group met in person for the first time during the convention.

College sports leaders are not the only ones trying to influence lawmakers. The National College Players Association, an advocacy group, produced a paper earlier this month, urging lawmakers to not be swayed by the NCAA’s messaging.

“That’s our No. 1 fear,” said NCPA executive director Ramogi Huma, a former UCLA football player.

The NCPA’s 16-page report lays out what it believes is the best way for athletes to be permitted to compensated for their names, images and likenesses. The group has also partnered with the NFL Players Association in the hopes of providing group licensing opportunities to college athletes.

“We’re going to get some help in D.C.,” Huma said, referring to the NFLPA. “The lawmakers in Congress need guidance.”

Emmert said he’s pleased with the progress this week though shared few details about how options were being narrowed.

“It’s hard to predict because I don’t know what the hell we’re going to do,” Smith said. “I don’t. I truly don’t.”