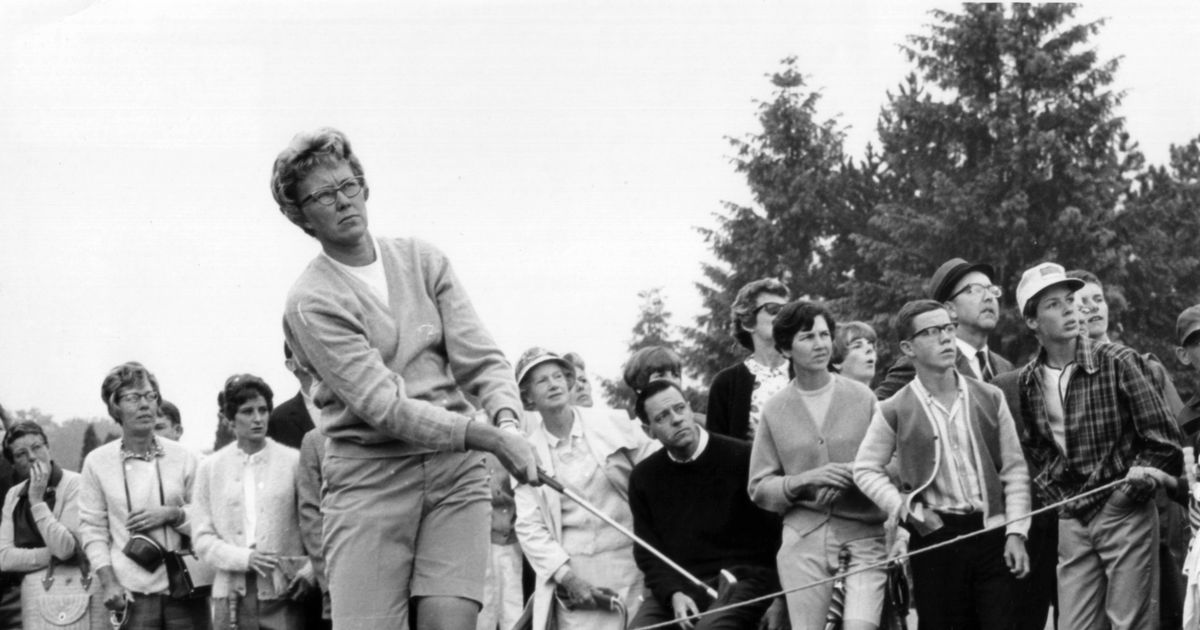

Mickey Wright leaves a legacy of big wins, beautiful swing

The swing was so fundamentally sound that it got the attention of anyone who knew and cared about golf, even those considered to be among the greatest to ever play.

The appeal was so strong that it carried an entire tour, even as the attention became suffocating. The rate of winning was unprecedented. No one had ever held all four major championships at the same time.

That was the essence of Mickey Wright.

Unlike the modern version — Tiger Woods — Wright was consumed more with seeking perfection in the golf swing than utter domination, although one led to the other.

“I was always practicing, and re-practicing, the same thing, over and over and over,” Wright said in a 2011 interview with The Associated Press. “You never get it. You just borrow it for a day or two. The feel of contact with a golf ball is unlike anything I ever experienced. And I loved it.”

Wright died on Monday of a heart attack at age 85, leaving behind a legacy that is measured as much by aesthetic beauty of her swing as her 82 victories and 13 majors during a comet-like career on the LPGA Tour.

She retired from full-time competition in 1969 when she was 34.

No telling how many times she could have won.

Wright won the LPGA Championship and the U.S. Women’s Open in 1959. That began a seven-year stretch in which she won 59 times and 12 majors. She won at least 10 times a year for four successive years, and she still holds the LPGA Tour record for 13 wins in a single season.

Ben Hogan agreed to a rare interview in 1984 with the late Rhonda Glenn, who said she was setting up two tape recorders when she mentioned that Mickey Wright passed along her regards. Glenn said Hogan leaned back in his chair with a big smile, looked into the distance an said, “Mickey Wright … greatest swing I ever saw. Boy, what a swing!”

Byron Nelson also said her swing was good as there ever was, and that came to define Wright.

“She was the best I’ve ever seen, man or woman,” Kathy Whitworth told ESPN in 2015. “I’ve had the privilege of playing with Sam Snead and Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer and all of them. And some of our ladies had wonderful swings. But nobody hit it like Mickey, just nobody.”

Judy Rankin recalls a different impact. She joined the LPGA Tour as a teenager when Wright was at the peak of her powers.

“In her time, because of her enormous skill, she got the LPGA a lot of kudos from men in the game,” Rankin said Monday night from her home in Texas. “That’s happening a lot more today. In that time, it didn’t happen at all. In Mickey, I think the men saw something else. That was really good for us.”

But only for so long.

Wright held such appeal that sponsors threatened to cancel tournaments if she didn’t play. And Wright realized if the tournaments went away, the other players had nowhere else to go. So she played.

Wright averaged 30 tournaments a year between 1962 and 1964. She drove from one stop to the next, and when she arrived at her hotel for the night, she would hit putts into a glass in her room to get feel back into the hands that had been wrapped around a steering wheel all day.

Back then, women did more than just show up and play. They promoted. Sometimes they had to help set up the course. Wright served as LPGA president in 1963 and 1964, two of her best years.

“The local people ran the tournaments, and the men at the club didn’t want us breaking records,” Wright said in 2011. “We started on the men’s tee, and they moved us back 10 yards every day. At that time, we were playing 6,400 yards.”

Did she stop too soon?

“I can go back and second-guess that one,” Wright once told the AP. “I should have played longer. AT the time, I had physical problems and had to play in tennis shoes. And then there was the pressure and the stress of having to win, of having won so much, of the press being disappointed if I didn’t win, having to be at tournaments.

“I finally had enough,” she said. “And I had accomplished what I had set out to do.”

For all her greatness, and her amazing collection of trophies, Rankin recalls a superstar who went out of her way to help.

“She had a presence you looked up to even more. She was a lovely woman,” Rankin added. “She was opinionated and smart, and she never said a bad word about anybody.”

Wright had a close circle of friends and lived a simple life without fanfare in retirement. The USGA made her the first woman to have her own permanent display in its museum — The Mickey Wright Room — alongside Hogan, Bobby Jones and Arnold Palmer. She donated some 200 mementos from over 40 years, including her synthetic mat.

For years, she would hit golf balls off that mat from her patio onto the 14th fairway of the golf course where she lived, and then she would pick them up.

Not long after she sent her mat off to the USGA, friends heard what she had done and sent her a new one.

“You know how it works,” Wright told Golf Digest in 2017. “Put out a mat, some balls and a club in front of a golfer, and the temptation to use them is going to be too much. So I keep my hand in, five or six balls at a time. Just enough to remain a ‘golfer.’”

That was her passion. She was as close to perfect as golf allows.