Pandemic puts first-year football coaches in deeper bind

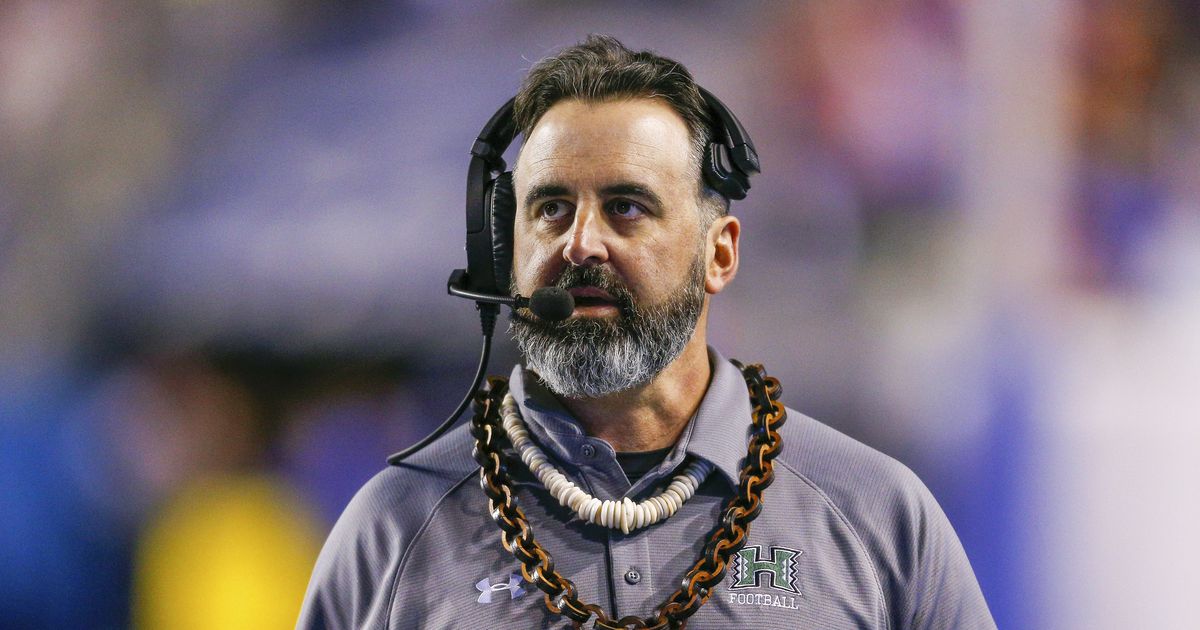

Nick Rolovich dived right in when Washington State hired him in January. Like all first-year coaches, he had to make up ground in a hurry.

There were assistants to hire, a roster to learn, players and administrators to meet. He had to reassure the most recent signees, begin work on securing future recruiting classes. Rolovich also had to set expectations for coaches and players while implementing new offensive and defensive systems.

Just when it seemed like things were up and rolling, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. The ensuring national shutdown hurt coaches across college football as they prepare for next season, but it was particularly difficult on programs with first-year coaches trying to build something from the ground up.

“I think most people would say it’d be not advantageous for a first-year coach,” Rolovich said. “We tend to think as coaches, whether it’s what the money has become, or the pressure of the job, you tend to always think you need to do more and more and more.”

Taking over a new program presents its own set of challenges. Coaches need all of spring to assess players and set a foundation, then build upon it in fall camp. Often, it’s still not enough time, leading to growing pains for the first season, maybe more.

The pandemic wiped out all spring activities in college athletics and could possibly carry over into the fall. That erases precious time for first-year coaches to strengthen relationships with players they’ve only known for a month or two, provide them with hands-on instruction and evaluate what they can do on the field.

A big portion of the teaching and assessing comes during spring football workouts. The NCAA allows teams to have 15 practices and a spring game in a span of 29 consecutive days, with most wrapping up by the end of April.

Some schools were in the middle of spring practices when the shutdown hit, others were just about to start. The loss of spring workouts makes it challenging for every program, but even more for teams with first-year coaches.

The Power Five first-year coaches include Jimmy Lake at Washington, Lane Kiffin at Ole Miss, Mike Norvell at Florida State, Baylor’s Dave Aranda, Missouri’s Eli Drinkwitz, Boston College’s Jeff Hafley, Mike Leach at Mississippi State, Sam Pittman at Arkansas, Michigan State’s Mel Tucker and Karl Dorrell at Colorado.

“I’d be lying if I said that doesn’t hurt us,” Pittman said. “We know our players as well as we can in the short period of time that we’ve been together, but man, it would have been nice to see what they can do and how they react to coaching and how they react to techniques and things of that nature. We just weren’t able to do it.”

Coaches like Rolovich and Pittman, who was hired on Dec. 8, had a few months to begin molding their programs before the outbreak.

Dorrell had a few weeks.

A former Buffaloes assistant, Dorrell returned to Boulder on Feb. 23 after Mel Tucker left to become Michigan State’s head coach. Dorrell worked quickly to hire coaches, interview his players and begin laying the schematic groundwork.

Colorado’s spring football was suspended indefinitely three days before the first practice, leaving Dorrell and his staff no chance to work with their players on the field.

“I’m not looking at it as a detriment just because I’m new. I look at it like everybody’s dealing with this,” he said. “I know that they’re all under the same guidance and standards of what’s going on right now with our country, so from our perspective, we’re just going to try to maximize whatever chance we get with our players.”

Coaches across the country are trying to navigate the locked-down, no-football world of the pandemic, preparing for a season while not knowing when it will begin. Meetings between coaches, players and positional groups are done virtually as teams do the best they can to ensure they’re ready when football starts up again, whenever that is.

The first-year coaches are also using the time to get to know their players and make sure there’s still a connection when they’re allowed to return to the field.

“I’m working through our roster, calling about 15 or so guys a day and spending time with them, getting to know their families, getting to know their daily routine, getting to know their goals and their vision for themselves and their futures and how I can help with that,” Aranda said. “I think when it’s slowed down to the point to where it is now, it allows us to fill in that space and that time with people.”