40 years later, vote to skip Moscow Games still ‘horrible’

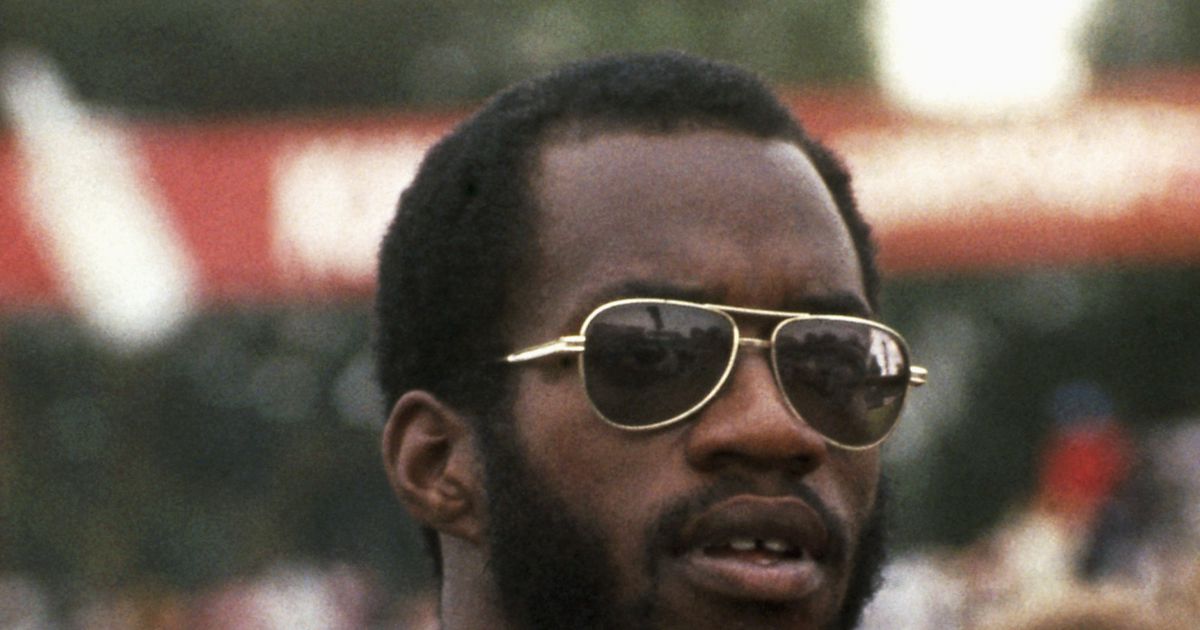

DENVER (AP) — By the time the news filtered to him, Edwin Moses had already left a promising engineering job to focus on a full-time career on the track.

He was lucky. He already had an Olympic gold medal hanging on his wall.

Hundreds of other American athletes would never get their chance.

They were part of the 1980 U.S. Olympic team — the team that never made it to the Moscow Games after President Jimmy Carter spearheaded a now-infamous first-of-its-kind decision to boycott the Olympics.

The full board of the U.S. Olympic Committee rubber-stamped Carter’s decision 40 years ago Sunday — April 12, 1980.

“I’d walked away from my career to get ready for the 1980 Olympics, and all was moot,” Moses told The Associated Press by phone. “So, it was horrible. For me, and for everyone.”

Moses said by the time the USOC’s unwieldy delegation of nearly 2,400 people met at the Antlers Hotel in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on a Saturday morning in April, with Vice President Walter Mondale in attendance, it was all but a done deal that the U.S. team would not be traveling to Moscow.

Carter had begun the push in late 1979, with the Soviet Union pressing a military campaign into Afghanistan.

In his 2010 memoir, Carter called it “one of my most difficult decisions.” Maybe more telling, as former USOC spokesman Mike Moran wrote in a recap of the events leading to the boycott, was an exchange the late 1984 Olympic champion wrestler Jeff Blatnick had with Carter on a plane many years later.

“I go, ‘President Carter, I have met you before, I am an Olympian,’” Moran said in his retelling of Blatnick’s story. “He looks at me and says, ‘Were you on the 1980 hockey team?’ I say, ‘No sir, I’m a wrestler, on the summer team.’ He says, ‘Oh, that was a bad decision, I’m sorry.’”

Forty years later, there is virtually no debate about that conclusion. And the lingering irony of this year’s games postponed by a year because of the coronavirus pandemic isn’t lost on Moses.

“As an athlete, you lose one of your cat’s nine lives,” he said.

There will be a handful of could’ve-been 2020 Olympians who will not make it to 2021, because of age, injury or a changed qualifying procedure.

Of the 466 U.S. athletes who had qualified for Moscow in 1980, 219 would never get to another Olympics, Moran wrote.

Most of those who did would compete in 1984 against a less-than-full field. The Soviets and a number of Eastern Bloc countries boycotted the Los Angeles Games in a tit-for-tat retribution to the U.S. move four years earlier.

Moses romped to a victory at the LA Coliseum in 1984, and he almost certainly would’ve won had the Soviets been there, too. He was the world-record holder and in the middle of a string of 107 straight victories in finals at 400 meters.

If there was any silver lining to the 1980 boycott, Moses believes it was the recalibration of the Olympic model.

During the years of the Moscow and Los Angeles boycotts and massive red ink from Montreal in 1976, the forces that had compelled Moses to quit his job — a profession unrelated to track and field — to retain his amateur status as an Olympian were exposed as unfair and unrealistic. The 1984 Games marked the beginning of the Olympics as a money-making venture and the beginning of the end of the strict rules regarding amateurism that put many Americans at a distinct disadvantage.

All good for those who were able to take advantage of it.

Many from that 1980 team, however, saw their Olympic careers shuttered without ever competing on the biggest stage.

“Nothing was ever done to celebrate the team, and a lot of those members aren’t around anymore,” Moses said. “We made the ultimate sacrifice in a sports world that no one was asked to do — and it was completely involuntary.”