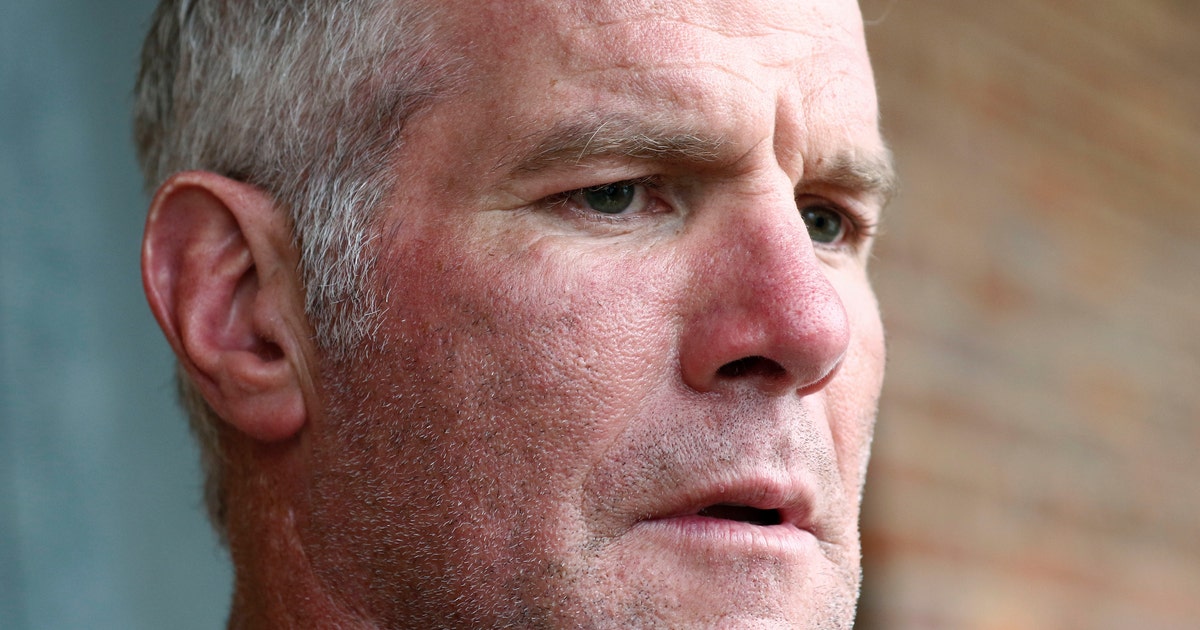

Auditor: Favre received welfare money for no-show speeches

JACKSON, Miss. (AP) — A nonprofit group caught up in an embezzlement scheme in Mississippi used federal welfare money to pay former NFL quarterback Brett Favre $1.1 million for multiple speaking engagements but Favre did not show up for the events, the state auditor said Monday.

Details about payments to Favre are included in an audit of the Mississippi Department of Human Services. State Auditor Shad White said his employees identified $94 million in questionable spending by the agency, including payments for sports activities with no clear connection to helping needy people in one of the poorest states of the U.S.

The audit was released months after a former Human Services director and five other people were indicted on state charges of embezzling about $4 million. They have pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trial in what White has called one of Mississippi’s largest public corruption cases in decades.

“If there was a way to misspend money, it seems DHS leadership or their grantees thought of it and tried it,” White said Monday.

White said the Human Services audit “shows the most egregious misspending my staff have seen in their careers.”

Payments to Favre were made by Mississippi Community Education Center, a group that had contracts with the Department of Human Services to spend money through the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. The audit says Favre Enterprises was paid $500,000 in December 2017 and $600,000 in June 2018, and he was supposed to make speeches for at least three events. The auditor’s report says that “upon a cursory review of those dates, auditors were able to determine that the individual contracted did not speak nor was he present for those events.”

Favre, who lives in Mississippi, faces no criminal charges. The audit report lists the payments to him as “questioned” costs, which White said means “auditors either saw clear misspending or could not verify the money had been lawfully spent.” The Associated Press on Monday sent questions to Favre by text message and left a message for him with his longtime agent Bus Cook, and Favre did not immediately respond.

John Davis was director of the Department of Human Services from January 2016 until July 2019, appointed by then-Gov. Phil Bryant — a Republican who also appointed White to office when a previous auditor stepped down. Davis was one of the people indicted; another was Nancy New, who was director of the Mississippi Community Education Center. Davis, New and the others indicted have pleaded not guilty and are awaiting trial.

The auditor’s report said that Department of Human Services leaders, particularly Davis, “participated in a widespread and pervasive conspiracy to circumvent internal controls, state law, and federal regulations” to direct grant money to certain people and groups. Davis instructed two groups that received grants, the Mississippi Community Education Center and Family Resource Center of North Mississippi, to spend money with certain other people or groups, the auditor’s report said.

White said the those two nonprofit groups received more than $98 million in Department of Human Services grants during the three years that ended June 30. Most of the money came from Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

White said the audit will be sent to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and federal officials will decide whether to sanction the state for misspending, White said.

The audit said the Mississippi Community Education Center awarded contracts for services to Davis’ relatives, including to a company owned by his brother-in-law and his nephew. It said that Family Resource Center used welfare money to buy one vehicle for more than $50,000 and another for nearly $28,000. White said the Department of Human Services should take the vehicles because they were bought with public money.

The audit said the Mississippi Center for Community Education spent $1.3 million to a group called Victory Sports Foundation to conduct three 12-week fitness boot camps. White said some participants paid but were not screened for eligibility for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families. The audit said state legislators and other elected officials took the fitness classes for free. White said Monday that the nonprofit group is responsible for the questioned spending, not the participants.

____

Associated Press sports writer Arne Stapleton contributed to this report from Aurora, Colorado.