These 5 charts show the pandemic’s devastating effect on working women

Overall, more than 22 million jobs were lost in March and April, and in the seven months since then just over half of those jobs have returned. But as of November, a gap remains: women held 5.3 million fewer jobs than they did before the pandemic began in February, compared with a 4.6 million shortfall for men.

What explains that disparity? First and foremost, the pandemic hit services sectors that require face-to-face contact harder than others. Women make up the majority of workers at businesses like restaurants, hotels, outpatient doctors’ offices and clothing stores — all of which steeply cut jobs early in the pandemic and have yet to fully recover. To be sure, men lost thousands of jobs in those industries, too — just not as many as women.

Meanwhile, for women fortunate enough to stay employed during the pandemic, things haven’t exactly been smooth sailing either. Millions work on the frontlines of the crisis: Women make up 77% of the workers in America’s hospitals, for instance, and around 74% of employees in K-12 schools. They’re caring for patients and educating children under enormous stress and personal risk of contracting the virus.A lack of child care has compounded these challenges for workers who are also parents, especially those with young children. In the first two months of the pandemic, day care centers cut 35% of their staffs. (This also is a female-dominated sector: 93% of day care employees are women.) While some rehiring has taken place since the spring, a recovery is far off. As of November, jobs were still down 17% in the sector, compared to February. This means parents have far fewer child care options than before the pandemic. For those who want to return to work, it will be more difficult — and in many cases, more expensive — to find child care.

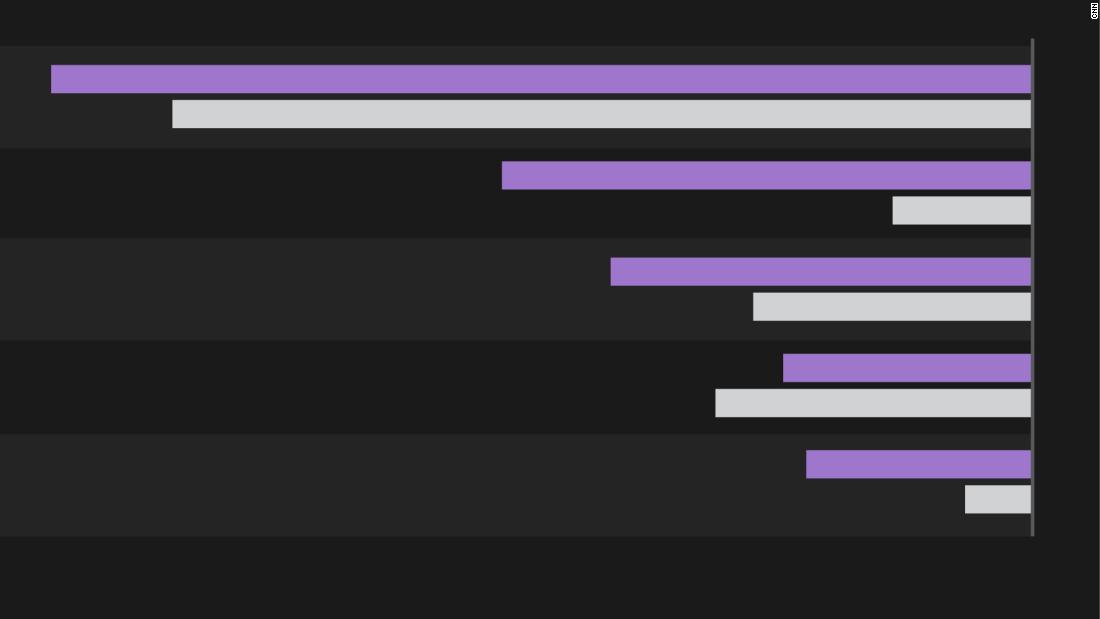

As schools and day cares shuttered, early studies show the care responsibilities at home have not been evenly shared. Women have taken on more of the child care responsibilities, including supervising distance learning, than their male partners. This burden has forced some women to drop out of the labor force altogether — at least for now.When economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas analyzed recent labor data, they found a significant disparity in how mothers and fathers responded to the pandemic’s strains on child care and their jobs. From February to September, the labor force participation rate of women with children under age 13 fell by 3 percentage points, compared to just a 1.8-point drop for women with no children. For men, however, the presence of children at home made little difference in their behavior. (Participation fell by 1.4 percentage points for men without kids, and 1.2 points for those with kids).

In their analysis, the Dallas Fed economists also found that among women with children, Black and Latina women dropped out of the labor force at higher rates than White women. Black women with children have had it worst of all demographic groups, with their participation rate declining by 6.4 percentage points between February and September.

“This is particularly disheartening,” the economists wrote, noting that the results suggest Black women’s labor prospects are being disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and the lack of child care. It also marked a major reversal: In the five years prior to the pandemic, Black women had experienced large job gains.

At the current growth rate, it could take another 40 months for the job market to fully recover from the pandemic. Economists warn that the longer women and men are out of a job, the harder it is for them to return to the labor force as the economy recovers. The permanent loss of earnings — as well as career setbacks — could eradicate earlier progress made toward gender equality in the workplace.