Money, opportunity part of one-and-done’s winding past

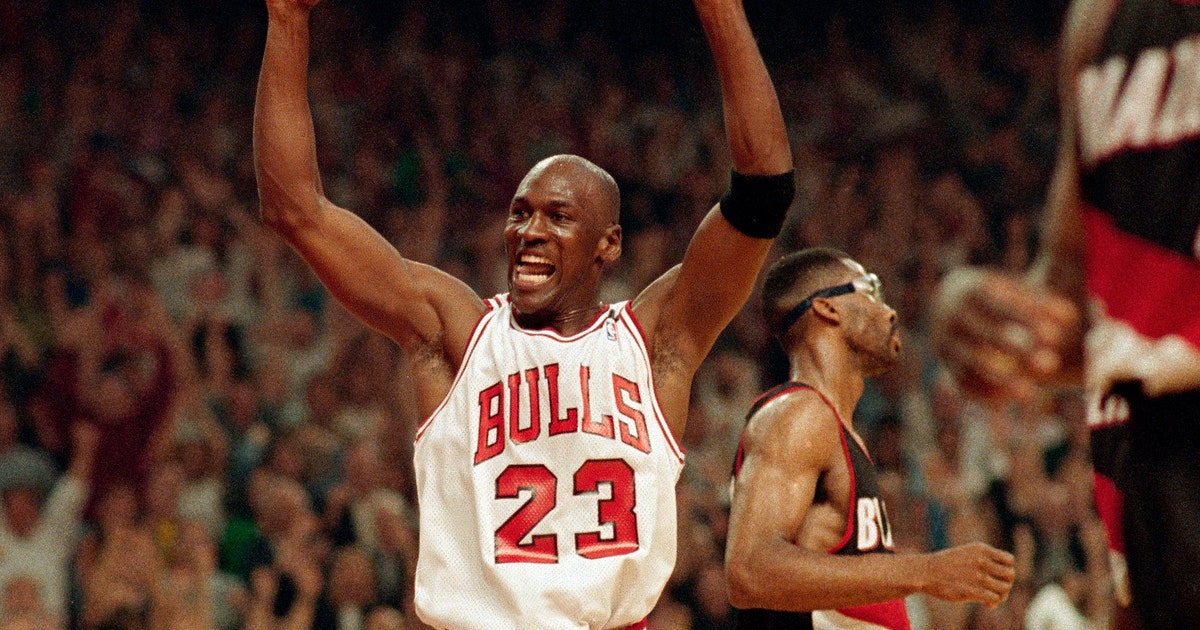

Spencer Haywood set the stage, Michael Jordan made it bigger and Kevin Durant super-sized it when he helped usher in the one-and-done era. Decades after those players made their groundbreaking departures from college, March Madness and the NBA’s mega-millions have taken all the novelty out of leaving early for the pros.

In the present era of one-and-done — a system that begat college programs that cater to kids in search of a one-year stopover instead of a diploma — the decision about whether to take off early for the NBA isn’t so much one of ‘if’ but ‘when’ for hundreds of players every year.

An Associated Press analysis of NCAA Tournament rosters over the last three decades shows the ever-expanding impact that early entry, and especially the one-and-done player, has had on both the college game and the NBA draft.

In 2005, the year before the one-and-done rule went into effect, there were nine high schoolers and one freshman drafted. Last season, there were no high schoolers, and 13 of the first 18 picks were one-and-done.

In the first year the AP studied, 1989, there were 13 early entries, five of whom played in the NCAA Tournament. Only one player drafted by the NBA that year was a freshman, Shawn Kemp. (The future six-time NBA All Star never played college basketball after eligibility issues at Kentucky and a transfer to a junior college.)

The rules could be changing again soon.

The NBA is considering doing away with the rule prohibiting players under 19 from being drafted, and the league is trying to come up with a new system. But it doesn’t want to return to the days of the 1990s and early 2000s, when unprepared high schoolers were drafted early, many of them never developing into stars or even role players. Whatever the change, it figures to have a considerable impact on the college game, though nobody is sure exactly what the impact will be.

“I think kids should go right to the NBA,” says Kentucky coach John Calipari, who has become the leading advocate of one-and-done, and the security it has brought to many college players and their families. “But there’s probably (only) five or six or seven that are ready to do that, and even half of those will probably spend time in the (developmental) G League.”

It wasn’t always like this.

Haywood’s decision to leave the University of Detroit in 1969 for the then-ascending ABA was considered revolutionary at the time. A year later, when he signed with the NBA’s Seattle SuperSonics, he won a Supreme Court case against the league, which had sued for violating the rule that players couldn’t enter the league until they were four years removed from high school.

Haywood’s victory set precedent, even if it didn’t exactly open the floodgates. Through the 1970s, a handful, sometimes up to a dozen, underclassmen entered each year into a league where a decent salary was only starting to reach into six figures. Some early entries from that era: Moses Malone, Bernard King, Reggie Theus.

Magic Johnson came out after his sophomore year, in 1979, and along with Larry Bird helped take the NBA to new heights.

By the time Jordan left North Carolina after the 1984 season — one of nine underclassmen, along with Charles Barkley and Hakeem Olajuwon, to declare that year — the NBA was introducing a salary cap, at $3.6 million a team, and the NCAA was expanding the field in its tournament to 64 teams.

Neither the pros nor what essentially became its unofficial minor league, college basketball, have looked back since.

Today, the cap stands at nearly $102 million and the number of players who came out early ballooned to 236 last year. Only 42 got drafted.

In between Haywood and 2018, early entry became more the norm than the exception.

In the early 1990s, the Fab Five and Michigan helped introduce baggy shorts and hip-hop into basketball. But in a wide-ranging recruiting scandal that resulted in most of their victories being wiped off the official books, Chris Webber, booster Ed Martin and the rest afforded college hoops a preview of the havoc that the growing influence of cash — with boosters, shoe companies and club coaches all playing a role in its distribution — could wreak on the sport.

With no restrictions and plenty of opportunities, high schoolers started taking the dip more regularly. But for every Kevin Garnett — the player who triggered the teens-to-NBA onslaught in 1995 — or LeBron James, there were even more like Kwame Brown, a top pick who turned into a bust or, even worse, Taj McDavid, who thought he could go from high school to the NBA, but never got a sniff.

That brought about the one-and-done rule.

Established in 2006, the year before Durant entered the draft and helped push the issue to the front-and-center of the basketball conversation, the rule forced players to wait a year after high school to enter the NBA. Most chose to use that year playing college ball, and Calipari wasn’t the only coach willing to cater to them.

These days, “one-and-done” is often used as catch-all for everything wrong with college basketball.

With the FBI getting involved in sorting out the connection between money, shoes and hoops — a job many think the NCAA should be doing instead of law enforcement — the NBA is rethinking one-and-done, trying to come up with a system that will better serve the game.

“It’s going to happen,” says Duke coach Mike Krzyzewski, one of those who has taken greatest advantage of the system.

A new framework could be in play by the 2022 draft. But what that system will bring is the multimillion-dollar question hovering over the game for the next three years.

“Tell me the environment that we’re going to be in,” Krzyzewski said. “We don’t know that environment. I don’t know how a youngster will be taken care of.”