Famed Indian climber nearly died on peak where team was lost

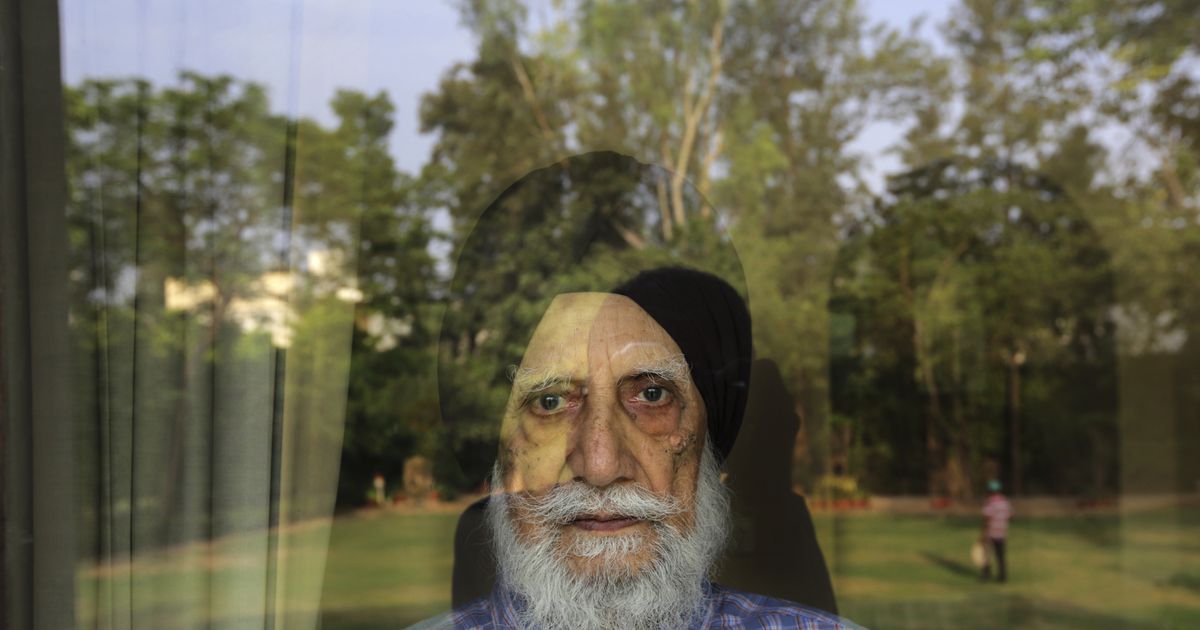

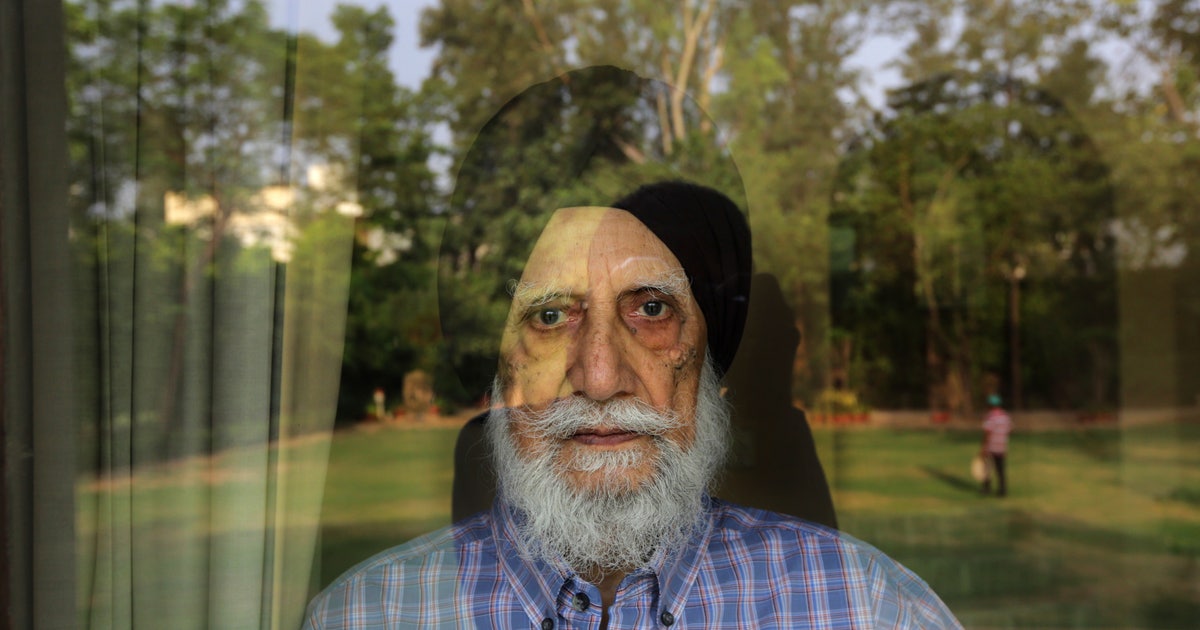

NEW DELHI (AP) — To Manmohan Singh Kohli, who led the first Indian team to the peak of Mount Everest, modern mountaineering bears little resemblance to the expeditions he headed decades ago.

Operators’ tight schedules and climbers’ lack of experience has added risks, diminished the adventure and resulted in more casualties, says the 88-year-old retired navy captain. With Everest becoming a bucket-list item that more and more people pursue, serious climbers are looking to less popular peaks to prove their skill.

That may have inspired an expedition that went missing in the Indian Himalayas to try an uncharted summit in a less traversed area. The eight members of the multi-national team led by a veteran British mountaineer are presumed dead in an avalanche.

After Kohli led nine Indian climbers to the top of Everest in 1965, he became a celebrity. He joined India’s state-owned airline to travel around the world to speak about the endeavor, which, at the time, had only been attempted by a handful of people.

Fifty years later, a bustling commercial climbing industry has sprung up in Nepal, pushing down costs and providing services — like porters from the ethnic Sherpa community who carry oxygen tanks, fix ropes and pitch tents.

It’s turned what once was a rare and incredible feat into “high-altitude tourism,” said Kohli, who nearly died on Everest in an unsuccessful ascent in 1962. “The adventure part of climbing has disappeared,” he said.

The government of Nepal issued 381 Everest permits this year, a record number that resulted in climbers getting caught in “climbing jams” on the world’s highest peak. Nepal estimates 700 climbers including Sherpas were on the mountain this May.

The crowding caused delays in the so-called “death zone” from Camp 4 to the peak where, because of the altitude, climbers have just hours to reach the top before they are at risk of a pulmonary edema, when the lungs fill with liquid. Eleven climbers died this season, the biggest death toll on Everest in four years.

“There are crowds there, so many teams going, that feeling of being lonely and planning your own adventure, that instinct has disappeared,” Kohli said in an interview.

British mountaineer Martin Moran took his doomed expedition to notoriously technical and avalanche-prone Nanda Devi East, a 7,434-meter (24,390-foot) peak which, along with its slightly higher twin Nanda Devi Main, rises from the center of a ring of icy peaks in the Kumaon Himalayas mountain range.

In 2015, Moran and fellow British mountaineer Mark Thomas set out to chart a new route along the northeast ridge of the peak. Just about 500 meters (1,650 feet) short of the top, Moran and Thomas reached a razor-thin edge with soaring drops on both sides, and decided to turn back.

Moran returned this May to lead an expedition to Nanda Devi East over the established route along the mountain’s southeastern ridge, according to their online itinerary on Scotland-based Moran Mountain’s webpage.

The $8,140, 35-day expedition offered “a chance to climb one of the greatest and most challenging peaks of India,” the itinerary said.

In addition to Moran, the team included three British nationals, John McLaren, Rupert Whewall and Richard Payne; two Americans, Anthony Sudekum and Ronald Beimel; and Indian liaison officer Chetan Pandey, according to Indian Mountaineering Foundation spokesman Amit Chowdhary.

Many mountaineers have lost their lives on the mountain, which has only been successfully climbed a handful of times.

“In comparison with Nanda Devi East, Everest is a picnic,” said Maninder Kohli, Captain Kohli’s son and an avid trekker who manages risk assessment for the Indian Mountaineering Foundation, the group that approves expeditions.

Manmohan Kohl tried and failed to summit Nanda Devi East, including an attempt in 1964 before he took the successful expedition of nine mountaineers to the top of Everest.

During the 1964 expedition, Kohli survived two avalanches and two precipitous falls.

Moran had summited Nanda Devi East before. It’s unclear why in May he chose to lead his expedition first toward a 6,477-meter (21,250-foot) unnamed, unclimbed ridge, according to a statement by the company.

Kohli, a winner of India’s top honor for athletic achievements for his mountaineering feats, recognizes the draw for mountaineering purists.

“It’s a bigger challenge, something which nobody else has done. If you do it, you become a pioneer,” he said.

As Moran headed up with his team, Thomas remained at base camp with another, four-member trekking group. Their last contact with Moran’s expedition “intimated that all was well and a summit bid would be made,” the company’s statement said. “It’s not entirely clear what happened from this point onwards.”

Thomas set out to search for the missing climbers after radio updates ceased on May 26.

He followed a trail left by the missing climbers that dead-ended in an avalanche, and sounded an alert. Thomas and the other trekkers were evacuated from base camp on Sunday. On a flyover mission, Thomas and other searchers again spotted the trail but not the climbers.

“They could see from the helicopter footmarks of the team but nothing else,” said Chowdhary.

On Monday, Indian Air Force pilots spotted five bodies by air that authorities believe were some of the missing climbers, since no other expeditions were underway. The three other climbers were also presumed dead, said Vijay Kumar Jogdande, an Uttarakhand state official.

Kohli’s perilous attempt to summit Nanda Devi East in 1964 was organized to select a team for the 1965 Everest climb, India’s third and ultimately successful mission.

According to Kohli’s 2003 book “Miracles of Ardaas: Incredible Adventures and Survivals,” his group set out to scale both Trisuli, a 7,120-meter (23,203-foot) peak, and Nanda Devi East.

On Trisuli, an avalanche swept down, making further progress impossible. Kohli and the others then set out for Nanda Devi East, but had to abandon the attempt in a strong blizzard. During their descent, one of the climbers slipped in the deep snow and set off an avalanche that sent them tumbling 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) downhill in just minutes.

“I had many narrow escapes like that, but just by good experience and good decision-making, we survived everywhere,” he said. “Nobody ever died on my team.”