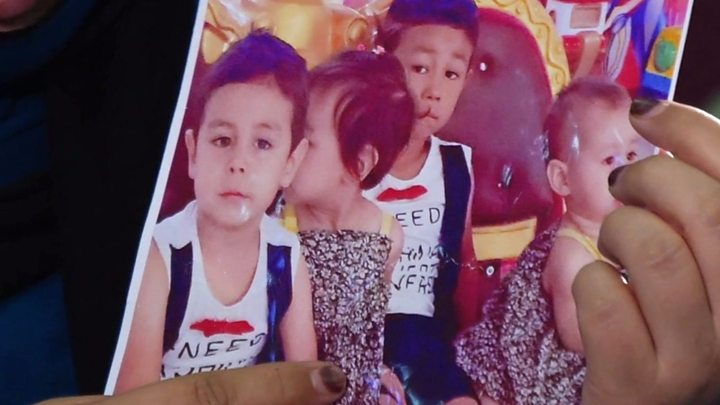

Children separated from parents by China’s Xinjiang camp system, research claims

According to independent researcher Adrian Zenz and the BBC, children are being placed in “highly secured, centralized boarding facilities,” whether or not they have other relatives who could serve as guardians. Zenz, a German researcher who has emerged as one of the leading experts on China’s vast system of camps targeting the Muslim Uyghur minority in Xinjiang, drew on open-source, government documents, both state and private media articles, propaganda and evidence from former detainees.In one township where ethnic Uyghurs constitute a majority of the local population, government data show that “well over 400 minors have both parents in some form of internment, with many others having one parent interned,” Zenz wrote in his report, “Break Their Roots: Evidence for China’s Parent-Child Separation Campaign in Xinjiang,” he added. The report was published in The Journal of Political Risk.”Children whose parents are in prison, detention, re-education or ‘training’ are classified into a special needs category that is eligible for state subsidies and for receiving ‘centralized care.’ This ‘care’ can take place in public boarding schools or in special children’s shelters.”But the parents have, in some cases, been detained without charge or trial, according to a 2018 report from the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. And Zenz says that the children’s other relatives are not given the chance to provide custody for the children.Chinese authorities did not immediately respond to CNN’s request for comment on the report.Up to 2 million people are estimated to have been detained in Xinjiang since early 2017. Activists and former detainees have described mass camps in Xinjiang where inmates live in jail-like conditions and receive repetitive lessons in Chinese propaganda.The Chinese government says the “vocational” camps are intended to combat Islamic extremism, and state media reports there have been “no major terror attacks” in Xinjiang since the campaign began.Most accounts have focused on the fate of adults placed in the camps, but Zenz and other researchers warn of a parallel crisis of children being separated from their parents and channeled into state care. “Driven by multi-billion dollar budgets, tight deadlines, and sophisticated digital database systems, this unprecedented campaign has enabled Xinjiang’s government to assimilate and indoctrinate children in closed environments by separating them from their parents,” Zenz said. “This separation can take various forms and degrees, including full daycare during work days, entire work weeks, and longer-term full-time separation.”Open source information and statistics show that in some Uyghur-majority areas in southern Xinjiang, preschool enrollment has more than quadrupled in recent years, exceeding national growth rates by over 12 times, according to Zenz’s research. The youngest child placed in an “educational institution” was just 15 months old. Citing reports by security companies involved in procurement, Zenz said that many of the schools were highly secured buildings with surveillance systems, perimeter alarms, and “4-layered 10,000 Volt electric fences atop their high walls, totaling 26,600 meters in length, and segmented into 176 ‘defense zones’.”Speaking to the BBC, which commissioned part of Zenz’s research, a senior official with Xinjiang’s Propaganda Department denied there were many families where both parents had been detained. “If all family members have been sent to vocational training then that family must have a severe problem,” Xu Guixiang told the broadcaster. “I’ve never seen such a case.”On Twitter, Zenz described his findings as showing “detailed evidence for systematic, state-initiated parent-child separation, weaponized education (and) cultural genocide.” Uyghurs — a predominantly Muslim, Turkic-speaking ethnic minority who were historically the majority in Xinjiang — have long complained that their culture and religion were being marginalized by the authorities. For years, activists focusing on Uyghur language and culture have faced pressure and even detention, accused of spreading “extremism.” Zenz’s research comes amid extra tension in Xinjiang as the region marks the 10th anniversary of ethnic unrest in the capital Urumqi, when protests over attacks on Uyghur workers in southern China turned violent following a government crackdown. In the wake of that incident, all internet access to Xinjiang was cut off for almost a year and numerous Uyghur websites were taken offline permanently.