After more than 600 days shut out, Delhi’s students just want to go back to school

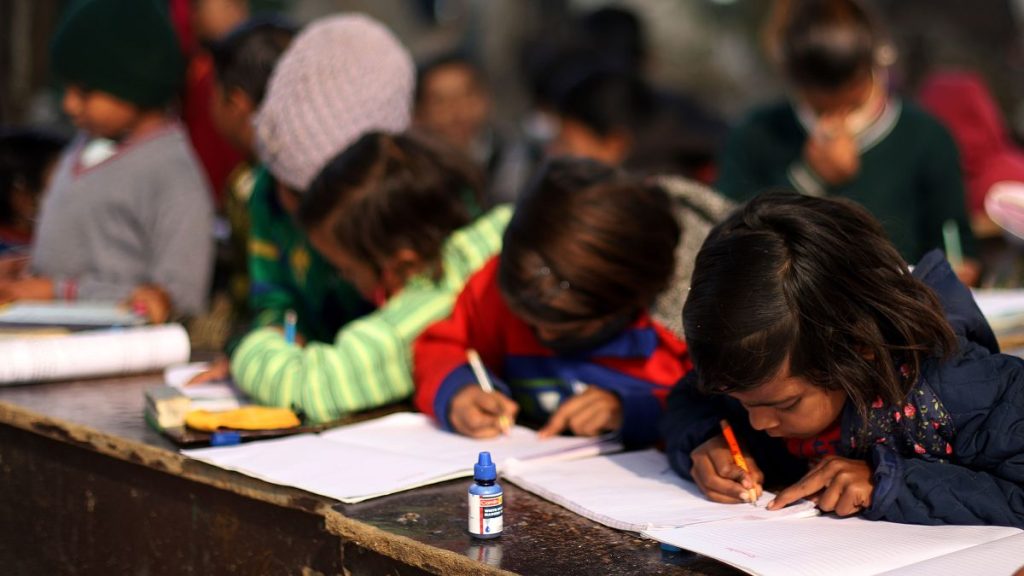

The ongoing mass closure, according to Mathur, is severely affecting their ability to learn. “Our little children have been out of school, no peer interactions,” Mathur said. “This isolation, and the lack of development that comes with that, is really quite critical.”The Delhi government ordered schools shut in March 2020 when cases started creeping up across the country. They have remained largely closed for nearly two years. It is one of the world’s longest school closures. And for a city with glaring disparities in development among its population, the prolonged learning loss has led to concerns it could increase poverty, reduce earning capacity, and result in mental and physical stress to millions. In Delhi alone, hundreds of thousands of children from lower income communities — who cannot afford laptops and live in cramped and unsanitary environments — are at risk of being denied an education altogether. In August, Mathur petitioned the state government to reopen schools. Nearly six months later, Delhi officials met Thursday to discuss a potential reopening.In the meeting, Delhi’s chief minister and his deputy proposed easing the restrictions to the capital territory’s Lieutenant Governor Anil Baijal, who has the power to implement the changes as head of the Delhi Disaster Management Authority (DDMA). While the officials agreed to ease some anti-epidemic measures, including revoking a weekend curfew and opening government offices, schools will remain shut.”We closed school when it was not safe for children but excessive caution is now harming our children,” Delhi’s Deputy Chief Minister Manish Sisodia wrote on Twitter on Wednesday. “A generation of children will be left behind if we do not open our schools now.” CNN has contacted Baijal’s office for comment but did not receive a response. Asia’s longest school lockdownIndia is second only to Uganda when it comes to Covid school closures. According to a report by the Schools reopened in November as cases stabilized but then closed again in December due to severe air pollution. And a surge in Omicron cases has kept them shut in January.The consequence has been “catastrophic” according to Shaheen Mistry, founder of non-profit organization Teach for India. “The impact is on multiple levels, the most obvious being learning loss,” Mistry said.According to Mistry, 10% of children in Delhi’s government schools have dropped out of education because of the pandemic and its economic impact on poorer families. “Child marriage has gone up, violence against children has gone up, nutrition is a huge issue as many of our children depend on school meals,” Mistry said. “The reality is we are coming onto two years of school closure. Kids have just lost so much learning.” But the problem isn’t limited to cities. A 2021 However, new, potentially fast spreading variants, such as Omicron, have led to renewed concerns worldwide over the risks faced by children in the classroom — and their role in spreading the virus.In recent months, the United Kingdom, parts of Europe and the United States, have all seen a rise in pediatric infections linked to Omicron. The uptick has threatened to disrupt plans to reopen schools. In the US, the Biden administration has insisted schools are “more than equipped” to stay open, though some elected officials are erring on the side of caution by delaying the new term.In India, more than two thirds of the population may already have some level of immunity against Covid-19, according to a July 2021 serological survey from the government-run Council of Medical Research (ICMR). “More than half of the children (6 to 17 years old) were sero-positive, and sero-prevalence was similar in rural and urban areas,” ICMR director general Balram Bhargava said in July.Vaccinations have also started for children above age 15, with more than 43 million having received their first dose as of Thursday. But as schools in other Indian states gradually reopen, Delhi’s classrooms remain shut. In a statement Wednesday, Delhi’s Deputy Chief Minister Sisodia said online learning can never replace offline studies. “During Covid, our priority was children’s safety,” he said, adding it was important to reopen schools.For Mathur, the issue goes beyond Covid. “We as parents believe that our children lack a voice, they lack a vote,” she said. “Someone needs to speak up on behalf of our children.”