Brazil transgender soccer team fights prejudice

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — On a late May afternoon, the Bigtboys soccer team played its first match, a friendly game on a flood-lit neighborhood pitch bordered by chain-link fencing.

With only four months of weekly training in the bag, the Bigtboys lost 9-1 to the more established Alligaytors. But just being on the field was unusually liberating to players on a squad that bills itself as Rio de Janeiro’s first transgender men’s soccer club.

And when striker Caique Rodrigues scored the team’s only goal, its supporters – mostly girlfriends and a handful of family members – screamed and shouted in excitement, temporarily drowning out their rivals’ more numerous, largely male fan base.

For the two dozen Bigtboys players, the training pitch is also one of the few places where they feel at ease and can talk about their experiences, good and bad, without fear.

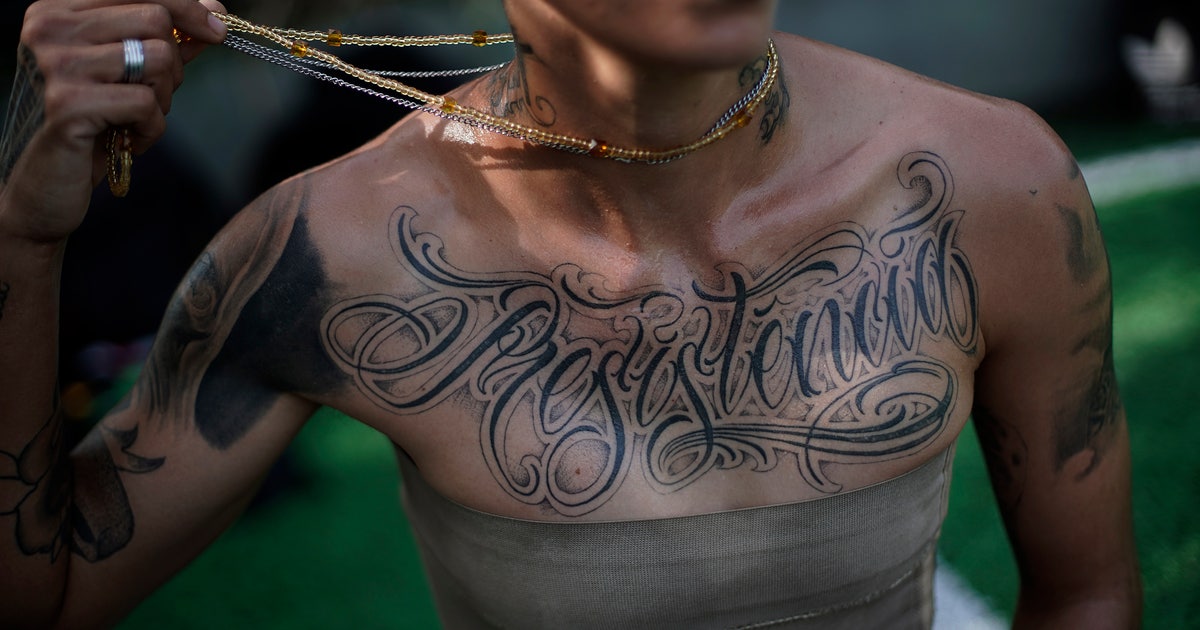

“People think we are fragile, that we are dolls, aesthetically changed,” said midfielder Robert Ismerim de Souza, 26, who works at city hall. “We’re here to win, to conquer a lot of things.”

Bigtboys, Alligaytors and other LGBT teams that have formed across Brazil are counting on the nation’s love of soccer to help fight prejudice amid a growing conservative tide. In late 2018, more than 57 million Brazilians voted for far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, who once said in an interview he would rather have a dead son, than a gay son.

Like many of his peers, Bigtboys midfielder Daniel Viana has struggled to make family and friends accept his identity. When still identifying as a woman, Viana came out as lesbian, leading to endless disputes with relatives. In an all-too-common scenario for transgender people, Viana wound up living in the streets. Within a few weeks, a group of five men assaulted him, raped him and got him pregnant.

“It’s difficult for us, it’s dangerous to walk in the street. We live in a society that is very prejudiced,” said Viana, now 28 and living with his girlfriend, during one of his weekly trainings.

The rights group Transgender Europe said 167 transgender men and women were killed last year in Brazil, making the country one of the world’s most dangerous for trans people.

Activists say the real numbers are likely to be far higher since hate crimes involving LGBT individuals are often not reported as such.

No laws specifically protect the country’s large LGBT community, though many have celebrated a Supreme Federal Court ruling stating that a law against racism also shields gay and trans people. It’s not final — the last votes are expected to be cast Thursday — but a majority of justices has already ruled in favor.

Even so, bills in Congress to outlaw homophobia have faced fierce opposition from an ever-growing number of conservative and evangelical lawmakers.

“Despite dozens of bills, only homophobic and transphobic discrimination remains without any kind of (legal sanction),” Supreme Court Justice Alexandre de Moraes said during a session in February. Another criticized the “evident inertia and omission” by lawmakers.

It’s not the first time the court has advanced gay rights in the absence of legislative action. It ruled in favor of same-sex unions in 2011, more than 15 years after a bill was first introduced to legalize them.

For players of the Bigtboys, the Supreme Court ruling isn’t a solution in itself, but a symbolic win, nevertheless.

“It was always a crime. We just did not have that kind of visibility; we were hidden,” said Ismerim, noting that not too long ago, gay and transgender people were considered mentally ill. “It’s not that I don’t feel scared anymore, but now I know that the state is on our side. We can live; before we were only surviving.”

Still, the rise of Bolsonaro and a socially conservative wave has alarmed the LGBT community.

“The government changed, and the doors started closing,” said Cristian Lins Silva, a 45-year-old photojournalist who put together the team after losing a bid for state representative in Rio de Janeiro last year. “I had enough of knocking on doors asking for help and not getting anything.”

Viana said he’d often felt suicidal and has found hope in the team, which is a sort of newfound family. His girlfriend of four months agreed.

The team “is showing the strength they have. They do what they like, each one with his dreams, his goals,” said Mariana Farias de Souza. “They are no different from anyone, not incapable of anything.”