Doc is in: Emrick not slowing down in his dream job

BOSTON (AP) — The Boston Bruins and St. Louis Blues’ morning skates are over and Mike Emrick stops to take a picture with some folks who ask for one.

A handful of broadcasters have taken the ice to re-enact a play from this bruising Stanley Cup Final. In the otherwise empty stands is a singular figure having a good chuckle at the retired players doing their best to go over the Xs and Os.

But Emrick doesn’t sit still for long. It’s a rare moment of pause for a man always in motion. A car comes to take him back to his hotel seven hours before the Game 2 so he can get a quick change of clothes for his on-air work and then it’s back to work.

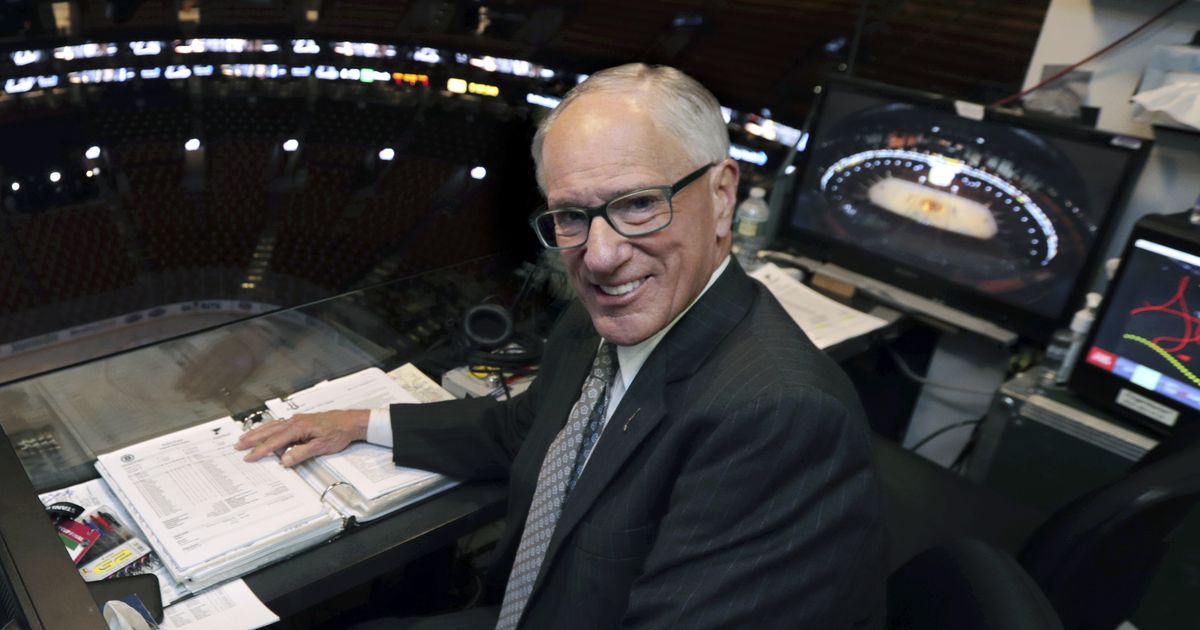

The man known as “Doc” because he has a doctorate in broadcasting is working the 21st Stanley Cup Final of his illustrious career. He has been honored by the Hockey Hall of Fame and is the voice of the sport in America, a rapid-fire storyteller who is beloved from the Shark Tank to Madison Square Garden. Colleague Kenny Albert calls him the Vin Scully of hockey, and the admiration level in hockey circles is just as great.

And at 72, still calling games on the NHL’s biggest stage, Emrick is in his prime and showing no signs of slowing down and stepping away from broadcasting the fastest game on ice.

“I really wanted to do it from the time I saw my first game, but a lot of people really want to do something and they don’t get to,” Emrick said. “When you have a job like that, you’re never working the rest of your life. So it’s been 46 years. I don’t know when it’ll end. God only knows.”

Emrick is so enthusiastic on the air during games that Rangers president John Davidson wonders now when watching if his former broadcast partner is going to come up for air. Not during the most important time of year for the sport he fell in love with as a kid sitting at Fort Wayne Komets games practicing calls in the corner on Wednesday afternoons with his reel-to-reel battery-operated tape recorder from the music store his dad owned.

Down time for Emrick comes mostly in the summer when he and Joyce, his wife of almost 41 years, go on camping trips to small towns mostly in Michigan, visit his brother and stepmother who still live in his Indiana hometown and watch his beloved Pittsburgh Pirates. During the season, they like going to lunch and at night sit together in the living room with their two dogs Joybells and Liberty — he’s watching hockey and she’s watching veterinarian shows.

“That’s a nice night for us,” Emrick says. “It’s probably not a life many people would find really exciting, but we enjoy it.”

Joyce and dogs are the centerpieces of Emrick’s universe that has plenty of room for the people who consider themselves lucky to call him a friend. That includes broadcast partners of various vintages Eddie Olczyk, Glen “Chico” Resch, Bill Clement and Davidson, who all have had Emrick in stitches laughing at a lunch at the Palace Grill diner in Chicago by the arena where he’s welcomed like family, or of him helping them through difficult times through talks or simply lighting a candle in a church for them.

“Just the support part of it from Doc is what is the most important thing,” said Olczyk, who leaned on Emrick when he was battling cancer. “He doesn’t even have to say anything, but if you just get a text or a picture or whatever, you know he’s thinking about you. Having been through it himself, that’s what friends do. I look at Doc as a friend.”

Emrick is 28 years removed from prostate cancer that he got the call about from Hershey Medical Center on a Friday night on the road in Montreal when he was the voice of the Philadelphia Flyers. He waited two days to tell Joyce in person — saying she was going to need to be a rock because he didn’t know what to expect — but right away he told Clement, who considers Emrick as close as a brother.

Clement’s admiration for Emrick as a broadcaster rivals only that for Doc the human being.

“Doc’s love for life and animals and excellence — Doc pushes himself to reinvent things and to be the best and to try new things and be different and yet not be a caricature,” Clement said Tuesday. When you listen to him on the air or see him on the air, he’s a real person. He’s a real person with an unbelievable gift that he grew himself to describe and to use the English language.”

Albert was a statistician for Emrick for games in the 1980s and used to write down quintessential Doc phrases he’d eventually take pieces of and sat behind him during the call of Sidney Crosby’s golden goal at the 2010 Olympics. Whenever Doc and Joyce Emrick decide he should call it a career, Albert figures the most likely person to succeed him as the top NBC Sports hockey play-by-play guy.

But there’s no replacing Emrick, who worked through a broken wrist from a fall during the 1992 Olympics and skipped 2002 altogether because one of their 4-year-old dogs Katie was sick and she meant the world to him. Liberty is the second Emrick dog named after the veterinary surgeon who tried to save Katie.

Along with exercising the dogs, Emrick is also doing a lot of sorting these days, sorting through 46 years of programs and other memories of his career and often tracking down addresses to send items to people when he thinks they or their children might want them. He and Joyce don’t have kids but have raised several dogs always referred to in press releases about Emrick as their canine children.

Emrick’s love for dogs, minor league hockey and the Pirates is far better known than his faith and involvement with hockey ministries, which is a huge part of his life that he doesn’t come through on the air.

“He doesn’t come across as super religious or come off as judgmental,” Resch said. “But that’s really what motivates him. He’s got a calling on a lot of different levels. … He doesn’t want to let anyone down.”

Emrick doesn’t know when he was “destined” to do this but like a player road the buses in the minors and climbed the ladder to get to this point as pretty inarguably the best hockey broadcaster in the U.S.

“He’s a guy that’s found a way to become a major part of sports in the United States,” Davidson said. “He’s Doc Emrick. He’s worked for everything. He doesn’t want to be treated like a superstar, but he is in his own field.”

Emrick certainly gets the superstar treatment around the rink or at the airport when people ask for a photo or perhaps an autograph. As long as it doesn’t keep him from his work, Emrick has always obliged, something his friends see as a central part of his character.

Now going year to year on the decision of whether to call another season, Emrick like his assured broadcasts has his reason why.

“I always do because I’ll miss it when it doesn’t happen,” he said. “It comes that time in the life of everybody.”