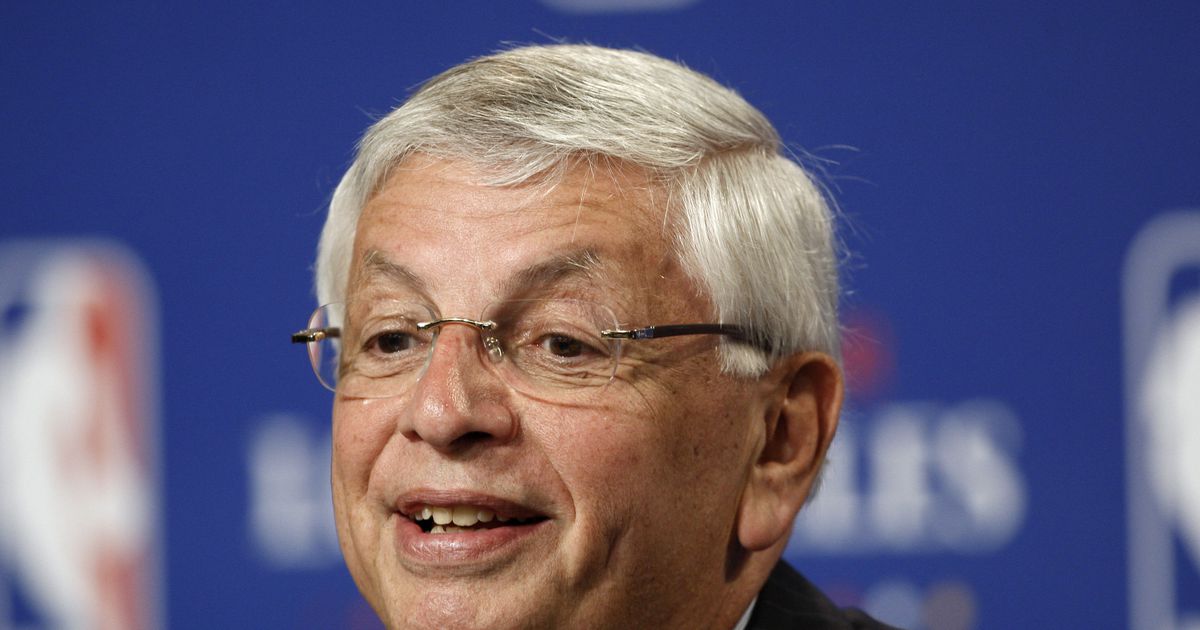

Former NBA commissioner David Stern dies at 77

NEW YORK (AP) — David Stern, the basketball-loving lawyer who took the NBA around the world during 30 years as its longest-serving commissioner and oversaw its growth into a global powerhouse, died Wednesday. He was 77.

Stern suffered a brain hemorrhage on Dec. 12 and underwent emergency surgery. The league said he died with his wife, Dianne, and their family at his bedside.

Stern had been involved with the NBA for nearly two decades before he became its fourth commissioner on Feb. 1, 1984. By the time he left his position in 2014 — he wouldn’t say or let league staffers say “retire,” because he never stopped working — a league that fought for a foothold before him had grown to a more than $5 billion a year industry and made NBA basketball perhaps the world’s most popular sport after soccer.

“Because of David, the NBA is a truly global brand — making him not only one of the greatest sports commissioners of all time, but also one of the most influential business leaders of his generation,” said Adam Silver, who followed Stern as commissioner. “Every member of the NBA family is the beneficiary of David’s vision, generosity and inspiration.”

Thriving on good debate in the boardroom and good games in the arena, Stern would say one of his greatest achievements was guiding a league of mostly black players that was plagued by drug problems in the 1970s to popularity with mainstream America.

He had a hand in nearly every initiative to do that, from the drug testing program, to the implementation of the salary cap, to the creation of a dress code.

But for Stern, it was always about “the game,” and his morning often included reading about the previous night’s results in the newspaper — even after technological advances he embraced made reading NBA.com easier than ever.

“The game is what brought us here. It’s always about the game and everything else we do is about making the stage or the presentation of the game even stronger, and the game itself is in the best shape that it’s ever been in,” he said on the eve of the 2009-10 season, calling it “a new golden age for the NBA.”

One that was largely created by Stern during a three-decade run that turned countless ballplayers into celebrities who were known around the globe by one name: Magic, Michael, Kobe, LeBron, just to name a few.

Stern oversaw the birth of seven new franchises and the creation of the WNBA and NBA Development League, now the G League, providing countless opportunities to pursue careers playing basketball in the United States that previously weren’t available.

Not bad for a guy who once thought his job might be a temporary one.

He had been the league’s outside counsel from 1966 to ’78 and spent two years as the NBA’s general counsel, figuring he could always go back to his legal career if he found things weren’t working out after a couple of years.

He never did.

After serving as the NBA’s executive vice president of business and legal affairs from 1980-84, he replaced Larry O’Brien as commissioner.

Overlooked and ignored only a few years earlier, when it couldn’t even get its championship round on live network TV, the NBA’s popularity would quickly surge thanks to the rebirth of the Lakers-Celtics rivalry behind Magic Johnson and Larry Bird, followed by the entrance of Michael Jordan just a few months after Stern became commissioner.

Under Stern, the NBA would play nearly 150 international games and be televised in more than 200 countries and territories, and in more than 40 languages, and the NBA Finals and All-Star weekend would grow into international spectacles. The 2010 All-Star game drew more than 108,000 fans to Dallas Cowboys Stadium, a record to watch a basketball game.

“It was David Stern being a marketing genius who turned the league around. That’s why our brand is so strong,” said Johnson, who announced he was retiring because of HIV in 1991 but returned the following year at the All-Star Game with Stern’s backing.

“It was David Stern who took this league worldwide.”

He was fiercely protective of his players and referees when he felt they were unfairly criticized, such as when members of the Indiana Pacers brawled with Detroit fans in 2004, or when an FBI investigation in 2007 found that Tim Donaghy had bet on games he officiated, throwing the entire referee operations department into turmoil. With his voice rising and spit flying, Stern would publicly rebuke media outlets, even individual writers, if he felt they had taken cheap shots.

But he was also a relentless negotiator against those same employees in collective bargaining, and his loyalty to his owners and commitment to getting them favorable deals led to his greatest failures, lockouts in 1998 and 2011 that were the only times the NBA lost games to work stoppages. Though he had already passed off the heavy lifting to Silver by the latter one, it was Stern who faced the greatest criticism, as well as the damage to a legacy that had otherwise rarely been tarnished.

David Joel Stern was born Sept. 22, 1942, in New York. A graduate of Rutgers University and Columbia Law School, he was dedicated to public service, launching the NBA Cares program in 2005 that donated more than $100 million to charity in five years.

He would begin looking internationally soon after becoming commissioner and the globalization of the game got an enormous boost in 1992, when Jordan, Johnson and Bird played on the U.S. Olympic Dream Team that would bring the sport a new burst of popularity while storming to the gold medal in Barcelona.

Stern capitalized on that by sending NBA teams to play preseason games against other NBA or international clubs, and opened offices in other countries. The league staged regular-season games in Japan in 1991 and devoted significant resources to China, and Stern’s work there would pay off in 2008 when basketball was perhaps the most popular sport in the Beijing Olympics.

Growth slowed near the end of his tenure. The worldwide economic downturn in the late 2000s all but wrecked his longtime hopes of expanding overseas and led to the second lockout, with owners wanting massive changes to the salary structure after losing hundreds of millions of dollars a year on their basketball teams, on top of losses in their personal businesses.

He helped get them, and the league was thriving again by the time he left office. Stern said he felt the time was right, confident that he had groomed a worthy successor in Silver, who had worked at the league for more than two decades.

Stern stayed busy, taking trips overseas on the league’s behalf, doing public speaking and consulting various companies. He was inducted to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 2014.