Guthrie’s barrier-breaking career celebrated in ESPN film

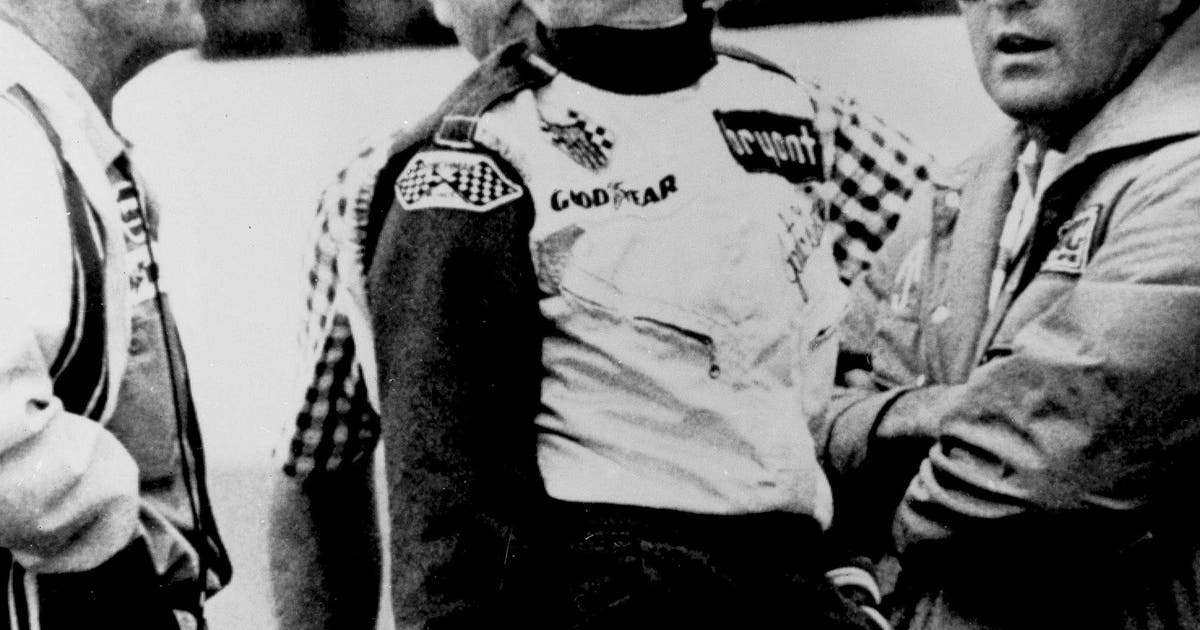

INDIANAPOLIS (AP) — Janet Guthrie did not receive a warm reception when she arrived at Indianapolis Motor Speedway 43 years ago. The former aerospace engineer had become a race car driver — unheard of during her era — and Guthrie wanted a spot in the Indianapolis 500, the biggest race in the world.

Her competitors wanted nothing to do with her and openly complained a woman was not suited for “The Greatest Spectacle in Racing.”

Guthrie was undeterred.

“As far as the men saying I couldn’t get it done, I figured they would learn better,” Guthrie told The Associated Press this week. “Did it bother me? Mostly I could laugh at it.”

Guthrie’s fight to become the first woman to qualify and race in the Indianapolis 500 is chronicled in the ESPN documentary “Qualified” scheduled to air May 28 as part of the 30 for 30 series. The film, directed by Jenna Ricker and premiered earlier this year at the South by Southwest Film Festival, airs two days after the Indianapolis 500.

Ricker, an ardent Indianapolis 500 fan, said she was compelled to tell Guthrie’s story because she knew so little about the pioneer.

“I was a fan of the Indianapolis 500 and I hadn’t heard of her and it ticked me off,” Ricker told AP. “I thought people should know this story, the first woman to qualify at the Indianapolis 500, then obviously the Daytona 500. Once I went down the Janet Guthrie rabbit hole, it was amazing to me — this was a story that needed to be told.”

Ricker discovered a goldmine of local television coverage, network broadcasts and rarely seen promotional films, plus home movies and Guthrie’s private photo and film collections. The material allowed her to create a film comprised almost entirely of archival material.

Guthrie first tried to make the Indy 500 in 1976 driving for Rolla Vollstedt, who wanted Guthrie even though she’d never raced an Indy car. Drivers were livid and USAC forced the 38-year-old to enter a race at Trenton to evaluate her readiness. It was an extremely difficult test for Guthrie because her male competitors raced her harder than necessary, and Guthrie had no room for error if she wanted to be approved for Indy.

She earned the right to qualify, but Vollstedt’s car wasn’t competitive and Guthrie had yet to impress anyone during her long, slow days battling the handling on her slow machine. A.J. Foyt graciously allowed Guthrie to turn some laps in one of his backup cars. Once inside the cockpit of something manageable, Guthrie was quickly up to speed.

Foyt didn’t offer her a chance to qualify one of his cars in the race and Guthrie didn’t make the field. Charlotte Motor Speedway promoter Humpy Wheeler saw all the attention Guthrie was receiving in Indianapolis and once she missed the race, he put a deal together to get Guthrie in the Coca-Cola 600 the same day as the Indy 500. It was Guthrie’s NASCAR debut after a month spent driving an Indy car and she finished 15th in her first race in a stock car.

Guthrie’s mind was still in Indy, though.

“Getting into A.J. Foyt’s backup car, are you kidding me? A car that’s worth about 100 or 1000 times more than everything I owned of value in the whole world?” Guthrie told AP. “That was big time. And when the yellow light came out and qualifying was about to begin and A.J. asked me whether I could go faster, I mean, I had done it once at trim, a one-lap qualifying deal, so he says can you go faster? And I said yes. I didn’t say, ‘I think so,’ I said yes because I knew I could.

“And then of course he decided not to let me qualify, and his crew was against it. So I had to wait a year. But what A.J. did, he changed a number of people’s opinions about what a woman might be capable of doing.”

Guthrie made it back to Indy in 1977, again with Vollstedt, qualified and became the first woman ever to race in the Indy 500. Her presence forced track owner Tony Hulman to change the “Gentleman Start Your Engines” command, something he was forced into by another pioneering woman.

Hulman had confided that because mechanics actually start the engines, the call didn’t need to be changed. So Kay Bignotti, who had a USAC mechanic’s license, said she would start Guthrie’s car.

The command these days is “Drivers, start your engines.”

Guthrie’s debut in the Indy 500 was a bust — her engine failed 27 laps into the race and she never had a chance. But she returned again in 1978 and proved her worth once and for all. She fielded her own car, qualified 15th and finished ninth.

In all, Guthrie ran at Indy three times and 11 total races in an Indy car. She ran 33 NASCAR races, including two Daytona 500s and squarely blames a lack of sponsorship opportunities in stalling her career just as she was a capable race car driver. Earlier this year, Guthrie was dropped from the list of five nominees for the “Landmark Award” for achievement in NASCAR in its Hall of Fame after three times on the ballot.

“You know, the Landmark Award is just a consolation prize for not having a Hall of Fame career, and I never had the sponsorship to give me that chance,” Guthrie told AP.

She and Ricker believe sponsorship woes are the sole reason Pippa Mann is the only woman in the Indy 500 on Sunday, while the Coca-Cola 600 in Charlotte, North Carolina, that night doesn’t have a single female driver in the field.

“When you have more women in a race, in a field, there is more chances of them winning, of them proving they belong on the track,” Ricker said.

At the end of the film, Ricker asks Guthrie how she’d like to be remembered.

“As a damn good racing driver,” she says, then pauses. “And a lady, I hope.”

But if she had to pick just one? Well, the answer was easy.

“A damn good racing driver,” Guthrie said.