How a failed social experiment in Denmark separated Inuit children from their families

Helene Thiesen was one of 22 Inuiit children separated from their families in Greenland 70 years ago.

Editor’s note: This story is part of CNN’s commitment to covering issues around identity, including race, gender, sexuality, religion, class and caste.

Seven-year-old Helene Thiesen peered out from aboard the passenger ship MS Disko, knowing she was setting sail from Greenland to a place called Denmark. What she could not understand is why her mother had chosen to send her away on that unhappy day in 1951.

“I was so sad,” Thiesen, now 77 years old, recalled to CNN. Rigid with sorrow, Thiesen was unable to wave back to her mother and two siblings, who were watching from the harbor off the coast of the Greenland capital, Nuuk. “I looked into (my mother’s) eyes and thought, why was she letting me go?”

Thiesen was one of 22 Inuit children who were taken from their homes not knowing that they would end up being part of a failed social experiment. Aged between 5 and 9 years old, many of them would never see or live with their families again, becoming forgotten about and marginalized in their native land.

At the time, Greenland was a Danish colony, and Greenlanders were suffering from high levels of poverty, low quality of life and high rates of mortality, said Einar Lund Jensen, a project researcher at the National Museum of Denmark.

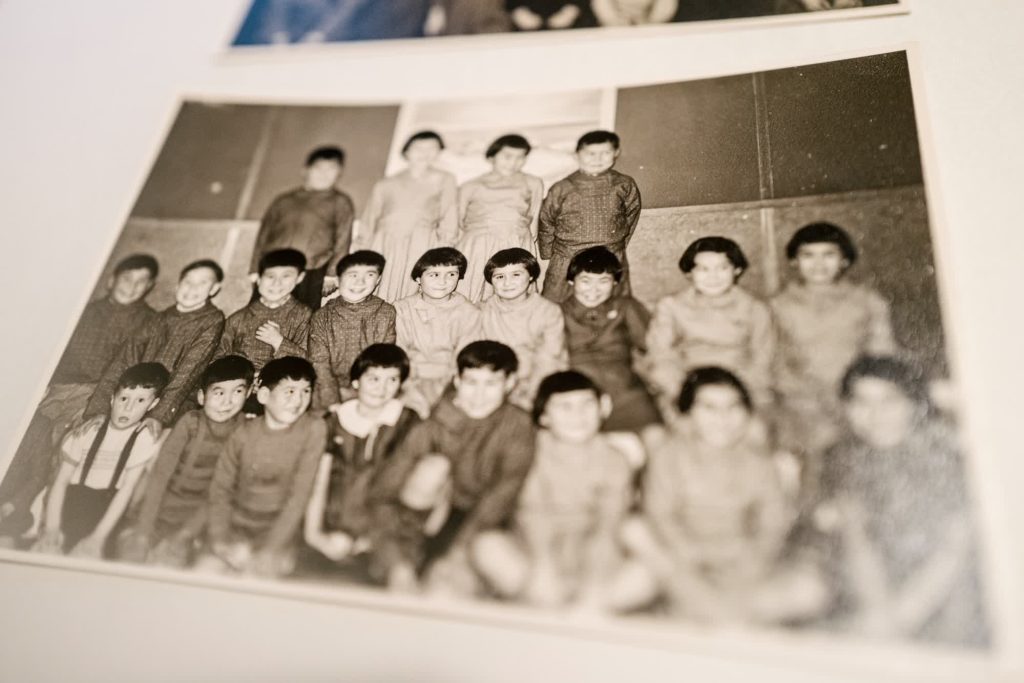

The Inuit children are seen at an orphanage back in Greenland wearing outfits made for them after a visit from Queen Ingrid of Denmark. Thiesen says the girls called them their “princess dresses.”

Denmark’s aim was “to create little Danes who would become the intelligentsia; role models for Greenland,” said Jensen, who co-authored a recent government-commissioned report investigating the experiment.

The Danish government felt compelled to modernize the arctic colony, hoping to hold onto their interests as post-war decolonization movements swept through the globe. They took up an idea from human rights organization Save the Children Denmark of bringing Inuit children to the country in order to recover from what were perceived as their bad living conditions, he said.

The assumption at that time was “Danish society is superior to Greenlandic society,” he added.

After a year and a half in Denmark, most of the children were returned to Greenland to live in an orphanage run by another charity, the Danish Red Cross, in Nuuk — separated from Greenlanders and their families and banned from speaking their mother tongue. CNN has reached out to the Danish Red Cross for comment.

Seen as strangers by Greenlanders, many of the children returned to Denmark when they became adults. Up to half of the group developed mental illness or substance abuse problems in later life, Jensen said. Many were unemployed and led hard lives, Thiesen said.

The Danish government “took our identity and family from us,” Kristine Heinesen, 76, who, along with Thiesen, is one of the six Greenlandic social experiment survivors alive today. Walking in a cemetery in Copenhagen where some of her friends from the experiment are now buried, Heinesen admits her life has been decent since her days in the orphanage. “But I know many of the other children suffered more growing up, and I think because we’re only six left of 22 — that tells the story very well,” she said, wrapped in a Greenlandic fur-lined coat.

Kristine Heinesen visits a cemetery in Copenhagen where some of her friends are now buried.

Save the Children apologized in 2015 for the part they played in the social experiment. The Danish government issued an apology five years later, after pressure from campaign groups, but has refused to compensate those who are still alive, said the lawyer of the victims, Mads Krøger Pramming. He filed a compensation claim of 250,000 kroner ($38,000) each in Copenhagen’s district court in late December 2021.

The six accuse the Danish state of acting “in violation of current Danish law and human rights, including the plaintiffs’ right to private and family life under Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR),” reads their claim.

In a statement to CNN, Denmark’s Minister of Social Affairs and the Elderly said the government was looking into the compensation claim.

“The most important aspect for the Danish Government has been an official apology to the now adult children and their families for the betrayal they endured. This was a major step towards redressing the Government’s failure; a responsibility no previous government had taken on,” Astrid Krag said.

“The government and I believe that recognizing the mistakes of the past is in itself crucial, and we must learn from these so that history is never permitted to repeat itself.”

The hearing is likely to happen in the next 10 months and “it is still our hope, that the government will settle the case and pay compensation before the hearing,” Pramming said.

After all the six victims have been through, “they don’t think an apology is enough,” he added.

Heinesen was just 5 years old when she was separated from her family.

‘Cultural eradication’

The aim of the experiment, which was greenlit in 1950, was to recruit orphans, but it was hard to find enough children, said researcher Jensen. The parameters were broadened to include motherless or fatherless households and 22 children were selected, even though many of them were living with their extended families or one parent, he added.

Thiesen’s mother, who was widowed, initially dismissed the request of two Danes to take her young daughter to Denmark, Thiesen told CNN. But she eventually agreed on the promise that Thiesen would get a better education.

As colonizers, Danes, who helped identify the children for the experiment, held authority in Greenland, Jensen explained.

It would have been hard for a Greenlander to refuse them at the time, Karla Jessen Williamson, a Greenlandic assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan and member of the Greenland Reconciliation Commission, told CNN.

“As with any colonized nation, the authorities (were) respected and feared; rebutting these authorities cannot be done,” she said.

According to the report Jensen co-authored on the experiment, there were doubts as to whether some of the parents were fully informed or understood what they were agreeing to.

In many ways, what happened to the children represents the devastating and deliberate effects of cultural eradication during colonialism, said Williamson. “In colonial times, there was an eradication of the uniqueness of culture, of the relationship with the land, the range of languages, spirituality — and these would have been done away with so that (the colonized) can be socialized into becoming part of the colonial state,” she said.

The children spent their first four months in Denmark at a holiday camp known as Fedgaarden.

On arriving to Denmark, the children were housed in Fedgaarden, Save the Children’s holiday camp on the southern Feddet peninsular, for four months. The children were banned from speaking Greenlandic — a dialect of the Inuit language — and were instead taught Danish.

The children were both terrified and amazed by their new surroundings. Heinesen was only 5 years old at the time and clearly recalls “all the trees — we don’t have any trees in Greenland, so I remember how tall and big they were.”

They were later placed with separate foster families for around a year. Thiesen did not feel welcome in the home of her first foster family. She had to wear an ointment for her eczema and was not allowed to sit on the furniture. “I was homesick every day,” she said.

Her second foster family were kinder, buying her a bicycle and doll, and treating her as part of the family.

When it was time to return to Greenland, six of the Inuit children remained in Denmark and were adopted by their foster families. The adoptions were “completely against the whole idea of coming back (to Greenland) and becoming the intellectual elite,” said historian Jensen. “In my opinion, it was a mistake,” he said.

‘Could not see anything through my tears’

They returned to Greenland in October 1952 and were placed in an orphanage run by the Danish Red Cross in Nuuk. According to the legal claim, custody of the children was transferred to the headmistress of the orphanage.

Thiesen only saw her mother a handful of times during the seven years she was at an orphanage.

Thiesen recalls seeing her family waiting for her by the quay in Nuuk. “I dropped my suitcase and ran to them, telling them everything I saw. But my mother did not answer me,” Thiesen said. It was because she was speaking Danish and her mother spoke the Inuit dialect of Greenlandic — a language Thiesen had lost the ability to understand.

Their reunion lasted 10 minutes. A Danish nurse looking after the children told her to let go of her mother because she now lived in an orphanage, Thiesen told CNN. “I cried all the way to the orphanage — I was so looking forward to see my town but I could not see anything through my tears.”

The orphanage was where 16 of the children lived. They were only allowed to speak Danish, were put in a Danish-speaking school, and contact with their families was limited or non-existent. No one told Heinesen that her biological mother died soon after Heinesen joined the orphanage, according to the legal claim.

Emphasis was placed on keeping in touch with the foster families, said Jensen. Thiesen’s mother was only allowed to visit her daughter a couple of times during the seven years Thiesen was there, the legal claim states.

It was psychologically traumatic “for these kids to be separated like that from Greenlandic society and their parents,” Jensen said. “Even those who (had family in Nuuk) said they were not allowed to visit their family. Sometimes the orphanage invited the family to coffee on Sundays, but the children were never given a fair chance to contact their families.”

Gabriel Schmidt looks through old photographs. He is one of the six social experiment survivors alive today.

They were enrolled in a Danish school and were limited from playing or interacting with Greenlandic children in the town. The only people the children were allowed to socialize with were prominent Danish families who lived in Nuuk, survivor Heinesen said.

Greenlanders began to consider the children as outsiders. Gabriel Schmidt, 76, one of the six from the social experiment who now lives in Denmark, told CNN that Greenlandic children in Nuuk would say: “You don’t know Greenlandic, you’re not Greenlandic,” and throw rocks at them. “But most of what they said I didn’t understand as I had lost my language in Denmark,” he said from his home.

Greenland was fully integrated into Denmark in 1953 and in 1979 it was granted home rule. In that period, Jensen said, Danish and Greenlandic authorities lost interest in the social experiment as Greenland’s infrastructure projects, business sector, and healthcare reforms took center stage.

‘Are you sitting down?’

By 1960, all the children had left the orphanage, and eventually almost all of them moved back to Denmark. For the six who are still alive, they say finding their sense of identity has taken a lifetime.

Schmidt returned to Denmark to live with his foster mother, where he eventually got a job as a solider in the Danish army. Speaking from his tidy home in Copenhagen, Schmidt said the army gave him a calling. “It really saved me. It gave me structure, friends and a purpose for my life, and in many ways that time was the best of my life.”

Schmidt said he was considered an outsider in his native Greenland.

Thiesen struggled to connect or forgive her mother, angry with her decision to send her away. “I thought my mother did not want me and it is why I was angry with her for most of my life,” she said.

It was only in 1996, when Thiesen was 46 years old, when she discovered the truth. The late Danish radio personality and writer Tine Bryld called Thiesen’s home with some devastating news. “She told me, ‘are you sitting down? I found something in Copenhagen, you have been part of an experiment,’” Thiesen said. “I fell to the ground and cried. It was the first time I had been told of this and it was so awful,” she added.

“I felt sad when I learned the truth,” Heinesen, who moved to Denmark in the 1960s and became a seamstress, told CNN. “You just don’t experiment with children — it’s just wrong.” In 1993, she put an advert in the local paper in Greenland that she was coming to visit and was looking for living relatives. “It was a great moment to be back and to visit — (it was) very emotional for all of us,” she said.

Thiesen has spent part of her adult life trying to reconnect with Greenland and her people. Her home in Stensved, a small town an hour and a half away from Copenhagen, is a testament to that attempt.

Sat at a dining table in front of a sideboard covered with snow white-colored tupilaq carvings, mythic Greenlandic Inuit figures meant to protect their owners from any harm, Thiesen told CNN that learning Greenlandic and writing her memoir has been part of her healing process.

It was facilitated by her second husband, Jens Møller, who is Greenlandic. Thiesen said he “gave me the biggest gift … to learn the Greenlandic language, but also he taught me fishing, hunting and all those things I had never done as a child, but which are key elements of the Greenlandic culture.”

It has not wiped away the enormous damage created by the social experiment but has, in some ways, helped her reconcile the pain that began aboard MS Disko in 1951. At least now she understands why her mother sent her away.

Thiesen sits at her home in Stensved, Denmark. She has reconnected with her Greenlandic heritage.