NFL At 100: Finding labor peace always a tortured process

NEW YORK (AP) — Lombardi Trophy. TV contracts. New stadiums. Huge profits.

Those are some two-word phrases that mean the most to NFL owners.

Another that should be listed: labor peace.

That has not been an easily attained objective, particularly since the NFL Players Association was created in 1956. There have been in-season and preseason strikes and lockouts and contentious negotiations. Costly court actions, too.

Even during Paul Tagliabue’s era as commissioner, when there were no disruptions, players pushed hard for freedom of movement and owners sought — usually with success until 1993 — to keep the status quo. It wasn’t until 17 years after baseball players won free agency that their football brethren got it, with some restrictions.

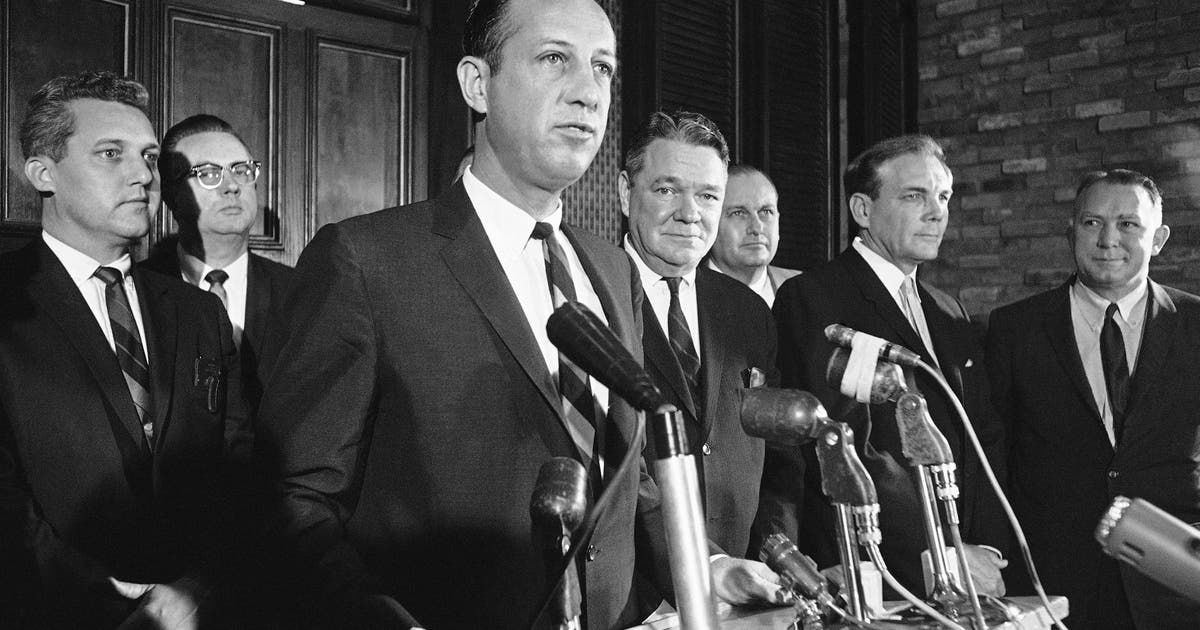

In order to ensure the 32 teams remain money-making machines — and can compete for that Super Bowl bauble — there must be a collective bargaining agreement with the players’ union. For two commissioners, Pete Rozelle (1960-89) and Roger Goodell (2006-present), that has proven a difficult challenge.

Under Rozelle, there were two strikes and three other work stoppages, though only the strikes affected the regular season. And, to be fair, Rozelle was not involved in negotiations with the union, then led by Ed Garvey; the NFL’s management council had full authority.

Goodell, of course, was leading the league in 2011 when there was a 132-day lockout of the players before a 10-year deal was reached.

Only Tagliabue avoided the black mark of a labor stoppage. He did so, in great part, because of a strong working relationship with Gene Upshaw, who served as the players’ union president or executive director from 1980 until his death in 2008.

“We respected each other,” Tagliabue says. “There was a credibility to what we did. We would say we were going to do something and then do it.

“We had an attitude, Gene Upshaw and I, of let’s get in there and see how many issues we can solve by negotiations, instead of a ‘heads I win, tails you lose’ approach. I think that attitude has disappeared for the most part.”

It rarely existed during Rozelle’s tenure, when Garvey went up against owners such as Hugh Culverhouse and Joe Robbie and Cowboys President Tex Schramm on the all-powerful management council. All could be acerbic and unbending, causing a deep separation between management and labor that led to several stalemates.

Those began before Garvey arrived on the scene in 1971. In July 1968, the NFLPA voted to strike and was locked out during training camp before an agreement was reached on pension benefits — the first CBA between union and league.

Two years later, with players locked out of training camp, the union again opted to strike, but a quick solution resulted in a four-year, $19.1 million agreement, though it didn’t address many of the union’s concerns, including freedom of movement for players.

In 1974, Garvey led another summer strike by players that ended with no new CBA. The management council’s strong opposition to free agency and the players’ fear of losing a paycheck once again hindered any progress.

“It’s hard to remember a time in the ’70s and early ’80s when there was good feeling between management and labor,” says Joe Browne, a key league executive and adviser to commissioners for 50 years. “We fought in the courts more than we negotiated at the bargaining table.”

But when the union won a key court battle in 1975 and ’76 that struck down the so-called Rozelle Rule that prohibited player movement, team owners simply refused to bid for players.

By 1982, the players found the resolve to strike when it truly mattered: during the regular season. They walked out on Sept. 21 and were gone for 57 days, shortening the season to nine games. And they won some significant gains: an improved salary and benefits package worth at least $1.28 billion over five seasons, and a settlement in which owners paid $60 million that essentially covered what players lost while striking.

But no free agency.

When that agreement ended, the union again struck after two weeks of the regular season — and was stunned when the league used replacement players. That led to many NFLPA members crossing picket lines, creating a nasty environment that ruined several team’s seasons — and did little to strengthen the union’s bargaining powers.

“The NFLPA has a difficult job,” says Don Yee, one of the most respected player agents who represents, among others, Tom Brady. “Irrespective of the leader, it has been historically difficult for football players to stick together during any kind of labor effort. If the players want change and progress, they will have to stick together and be willing to make the necessary sacrifices.”

The ’87 strike, embarrassing to all sides, was a major factor in Rozelle leaving as commissioner in 1989, ending a tenure generally acclaimed as the most successful in pro sports. He died in 1996.

“The decade of the ’80s was tough on Pete because the league was playing defense on so many fronts,” Browne explains. “There was a general malaise in the league for almost the entire decade.”

There were the two work stoppages, three years of battling the USFL, which then folded, and litigation over the Raiders‘ right to unilaterally move from Oakland to Los Angeles.

“Pete was physically out of the office a great deal during those months,” Browne adds. “Pete knew there never would be a time when all the league’s problems would be settled in a positive manner. It was enough to convince Pete to step down as commissioner in 1989 after three decades of seven-day work weeks on the job.”

Tagliabue already was deeply involved in NFL legal matters and was elected to succeed Rozelle, but insisted he lead all labor negotiations. It was a wise and fruitful move: His 17 years in charge resulted in zero work stoppages.

And in 1993, Tagliabue and Upshaw hammered out a ground-breaking CBA that included free agency and a salary cap, something only the NBA had at the time — and two provisions that previously faced intense opposition.

There were four key elements to the system, which Tagliabue says “made it work for everyone and made it something that could be sustained for decades.”

First was player movement with some rights of retention for the teams, something Tagliabue agreed with Upshaw was essential.

“Movement was important because under the old reserve clause good players could get stuck behind better players and never get a chance to play and prove themselves,” Tagliabue says.

Second, a semblance of market value for the players was established. There will always be a pecking order in which quarterbacks and pass rushers earn the most, but fair pricing had become attainable.

Third, the salary cap meant every team would end up with a comparable payroll, regardless of the market.

“No Siberias left in terms of getting paid,” Tagliabue says. “Obviously some players are going to be off the charts, but there would be no teams where players don’t want to go because payroll is half of what is elsewhere.”

Which meant, lastly, that “all teams should be able to compete, roughly with equal access to players with the draft and free agency and the salary cap,” he explains. “It was understood that competitive balance makes for the best product in most cities, and produces the most revenue. Every team can have a competitive season. And there are no dead-end jobs. That was the key and still is.”