NFL looking into high number of lower extremity injuries

PHOENIX (AP) — Next to torn ACLs, the most time lost for injured NFL players is due to hamstring and lower extremity problems, of which there are far more than the major knee issue.

So the NFL will place even more emphasis on examining hamstring, groin, foot, ankle and other such injuries, along with its heavy concentration on the knee.

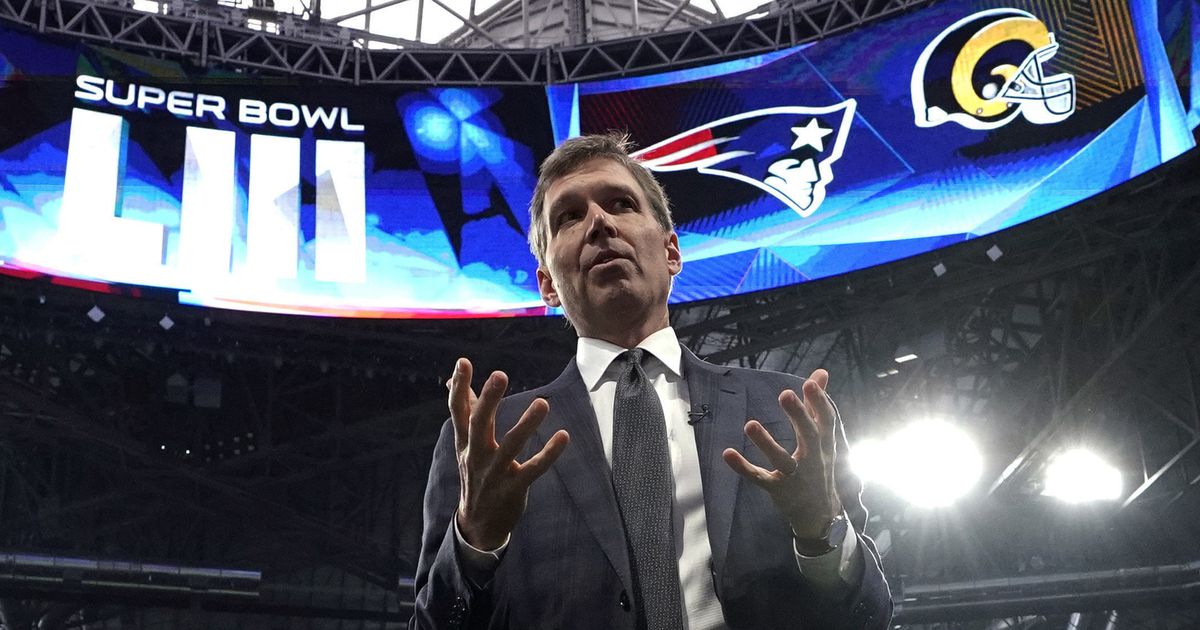

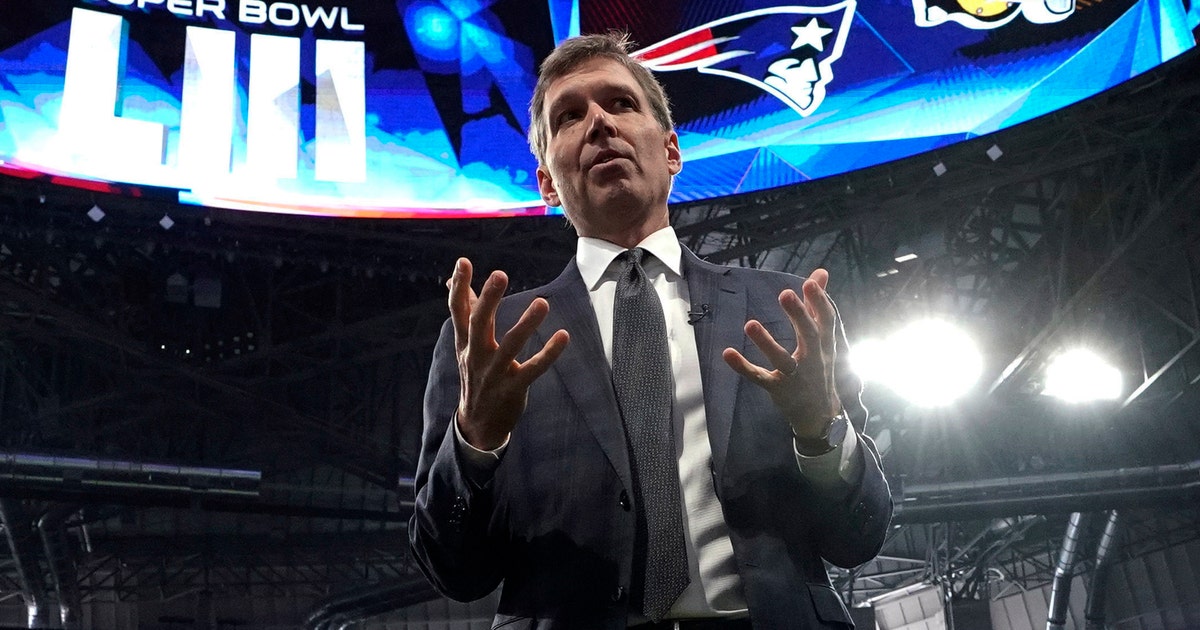

While reducing concussions remains the most critical player safety initiative — they were down 29 percent in 2018 — Dr. Allen Sills, the league’s chief medical officer, this week stressed the need to target the lower extremity injuries “the same was as with concussions.”

“We are thinking about injury burden,” Sills said. “Not only how many injuries but how long a player missed. We plan by the end of year in hopes of making substantial savings of time lost (for players) with those injuries,” Sills said.

Some of those injuries occur because players push too hard when they aren’t in the shape to do so, particularly those who report late to training camp — or not at all, and then come aboard during the season. That’s particularly true of hamstrings; it’s not unusual for observers to wonder how soon, not if, such players will struggle with such problems.

“It’s how you train and when and how much intensity you bring to specific times you train,” Sills explained.

The league will talk with team trainers and doctors, with exercise experts and researchers in a push to reduce what often are termed “nagging injuries.”

Sills and Jeff Miller, the NFL’s executive vice president of health and safety initiatives, spoke about a variety of injury and player safety topics at the owners meetings. They were most encouraged, not surprisingly, by the decrease in the number of concussions, with one exception: Things were static during preseason practices, when 45 occurred in 2017 and 45 happened against last year. Many of those were incurred by offensive linemen, Sills said, and were specific to blocking.

“We’ll be meeting with position coaches to look at how linemen are training in camp,” he said. “We will make all the teams aware of the data we collect.”

Factors for the reduction in concussions include enhanced rules prohibiting lowering the helmet, fewer kickoff returns (also due to rules changes); players making adjustments to the new or stricter regulations; and players switching to the highest-rated helmets in a survey conducted by the league and the players union.

Miller noted that half of the league has changed helmets and 74 percent of the players now wear helmets in the highest-approved (green) region of the survey and accompanying poster that is hung in every team’s facility. He credited training staffs, medical personnel, players, coaches and team owners.

“The posters certainly were able to change player behavior,” he said.

Same thing, Miller added, regarding lowering the helmet; the number of concussions were down from that act.

Concussions on kickoffs were down 38 percent in 2018 compared to the previous three seasons’ average. Indeed, Sills said all injuries on kickoffs went down, and his staff is now doing deep research into injuries on punts, which have been the second-most dangerous play. Ten percent of all major injuries, termed as eight days or more missed, came on punts.

The league banned blindside blocks on all plays on Tuesday, a short while after Miller and Sills made their presentation to the owners. There were as many as a dozen concussions annually due to that technique.

“As a former player and father of two that play ball, and having the opportunity to coach (youth football),” football operations chief Troy Vincent said, “this particular play, the blindside block, it ends careers, puts people on the shelf.

“That particular technique, I was taught that. To have that removed out of our game is significant.”

The NFL’s medical and research staffs aren’t limiting their work to what happens within the league, either. They are looking at data from other organizations such as the new spring league, the Alliance of American Football, plus the Canadian Football League and college teams.

“With more opportunities to learn and collect data,” Miller said, “it will yield a better outcome for everyone.”