School spirit: US colleges pave the road to track success

DOHA, Qatar (AP) — Nobody would think of asking Jamaicans, Kenyans or other winners to play “The Star-Spangled Banner” if they capture a gold medal at world championships next week.

Maybe their school’s fight song would be better.

When it comes to producing champions at the highest level of track and other Olympic sports, the U.S. colleges have every bit as big an impact as training systems in many an athlete’s home country.

To wit:

—At NCAA track and field championships earlier this year, around 230 of the athletes came from countries outside the U.S.

—And out of the 141 American athletes at worlds in Doha, all but four competed at a U.S. university at some point during their career.

“We are the minor leagues for our track and field in this country to get to the next level,” says Clyde Hart, the director of track and field at Baylor, who coached, among others, Olympic champions Michael Johnson, Sanya Richards-Ross and Jeremy Wariner.

In a strange way, it makes the college football games this upcoming weekend every bit as important as the sprinting and throwing when it comes to sustaining not only track, but every Olympic sport in the United States.

Of the 558 U.S. athletes who competed at the Rio Olympics, 439 came from the U.S. college system; of the 211 who won medals, 176 came from college. The bulk of the athletes — 327 of them — came from what are known as the Power Five conferences — the Pac-12, SEC, ACC, Big 12 and Big Ten — that have the largest TV football and basketball contracts and operate the largest sports departments.

The money schools bring in off football and basketball helps fund pretty much every other sport, but many of those programs struggle to stay afloat nonetheless. Between 1991 and 2012, for instance, the number of men’s gymnastics teams shrunk from 36 to 16. Men’s wrestling teams decreased from 110 to 77.

Well aware of how closely its success is tied to the NCAA, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee is strengthening its relationship with college sports and has been pushing for reforms that will make it simpler for athletes to pursue the Olympic track without jeopardizing their college eligibility. Financial pressures because of the NCAA’s strict rules about sponsorships have long been a concern. The USOPC formed a college advisory council in 2017 that consists of executives at Duke, Alabama, Stanford, Texas and the Big 12, among others.

Within the Olympic world, track and field is faring better than most sports. According to NCAA statistics, there were 286 men’s and 338 women’s track teams in Division I as of 2018, which marks a slight increase over the past decade — not surprising considering one of the foundations of Title IX is to offer the same number of opportunities for women to play college sports as for men.

Of course, this is something of a mixed blessing for those who bleed red, white and blue.

In Rio, all but four of America’s 129 track and field athletes were groomed in the NCAA. But those same schools are helping produce champions for other countries, as well.

For instance, five of the 42 Jamaicans who competed at the NCAA Championships in June will be in Doha this week. In another twist, Jamaica’s top hurdler, 2015 world champion Danielle Williams, is a volunteer assistant coach at Clemson, meaning she’s able to train there.

Germany, Canada, Nigeria and Grenada are among the countries that have athletes who will complete a ‘double’ of sorts this year by competing in both NCAA and world championships.

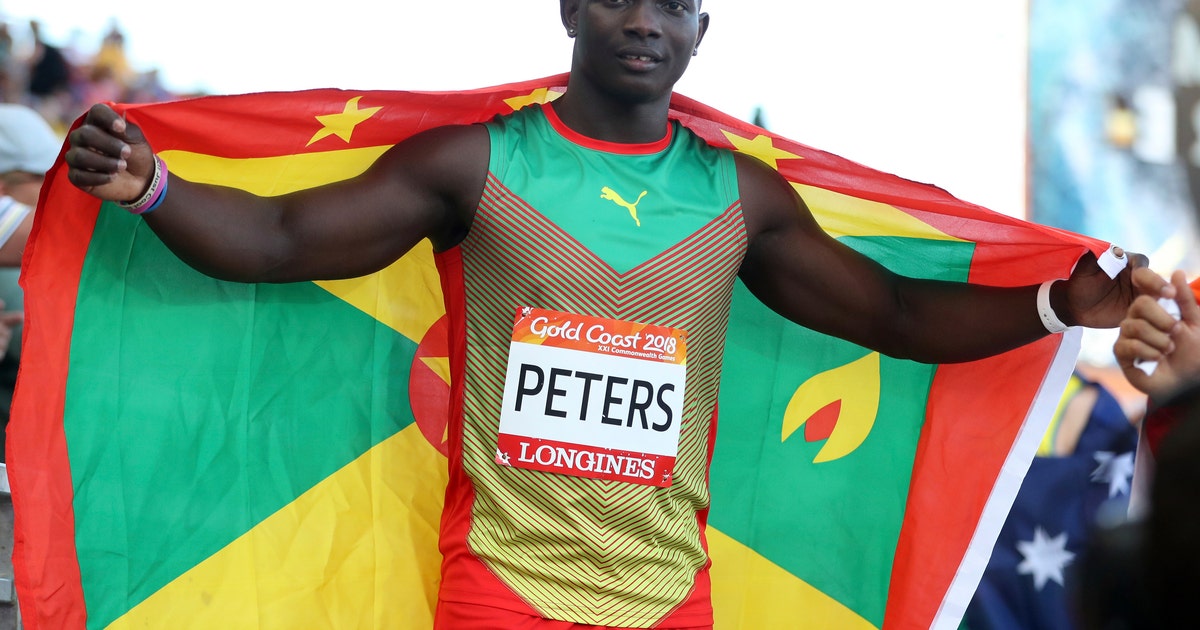

Anderson Peters holds Grenada’s national record in the javelin throw and is also the NCAA champion out of Mississippi State.

“I think it’s done a lot for me,” Peters said of the leap of faith he took when he enrolled in American college. “The facility is for sure 100 percent better than the facilities I had at home. The coaching staff, the treatment that I’ve been getting on my body has been pretty good. It really helps.”

Max Siegel, the CEO of USA Track and Field, says his federation and others work hard to improve the quality of the sport in all countries, not just the United States.

“We all benefit by collaborating,” Siegel said. “We take pride in that.”

No single entity represents that spirit better than the quintessentially American institution of college sports.

Of the 31 U.S. sports teams at the Summer Games in Rio, all but 11 had rosters with at least half its athletes’ roots in a college program.

None of those sports depends more on the colleges than track, which essentially uses the schools not only as a training ground, but as a scouting system to determine where athletes stand — both competitively and within their financial support system — when they get out.

The U.S. team compiled a record 30 medals at the 2017 world championships, and could be looking at a similar haul both this year and at next year’s Olympics.

“I’ve got to thank the American high school system and the American college system for giving us a great jump-start,” said USA Track and Field’s chief of sport, Duffy Mahoney. “We’re very fortunate that we embarked on that kind of operational philosophy umpteen years ago and we’re getting better at it.”