‘The Last Dance’ is set to make Michael Jordan real and present, instead of the myth he’s become

To anyone in high school or college, anyone in their mid 20s or younger, Michael Jordan is many things.

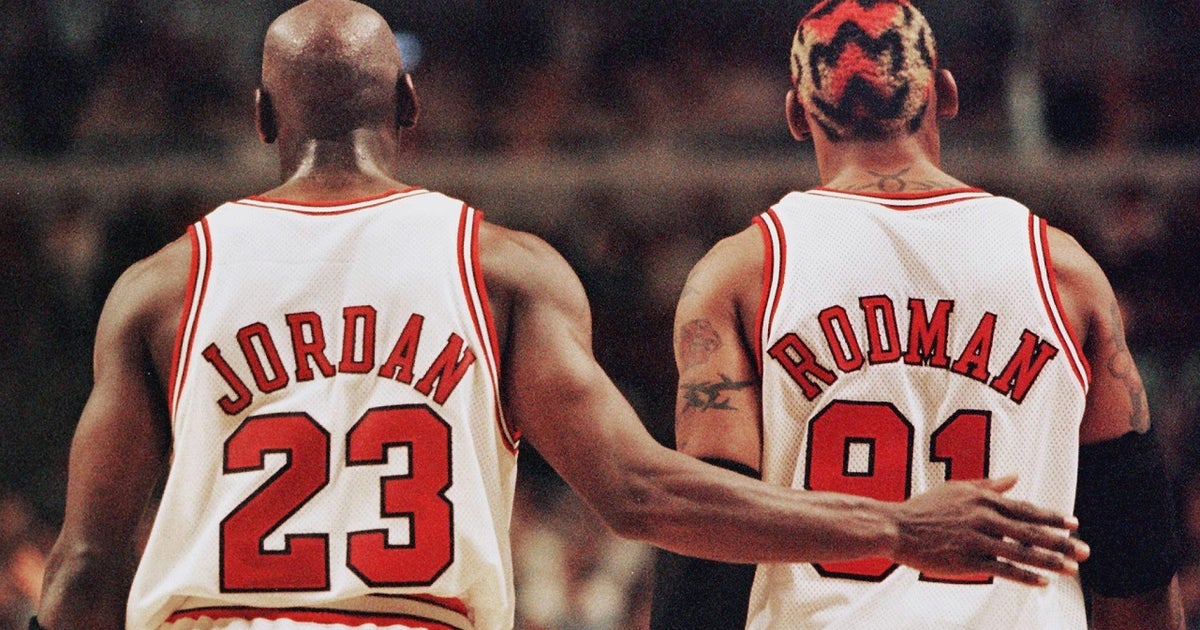

He is the greatest player in history, but largely as a film character from countless low-res YouTube clips. He is the Jumpman logo. He is a billionaire team owner. He is the guy who cried and got turned into a zillion memes. He is the lead of Space Jam. He is a set of jaw dropping statistics. He is the ghost hanging over each failed Chicago Bulls season.

He is iconic. His greatness is eternal — but it is not necessarily present.

That is about to change. Jordan, the man, not just the brand, is about to become known to a global audience in a way that, for all the fame and the accolades, has never happened before. He says people are going to hate him once they see “The Last Dance,” a 10-part docuseries that debuts on ESPN domestically and Netflix internationally on Sunday.

TONIGHT. #TheLastDance pic.twitter.com/NKGEOl2yuu

— NBA (@NBA) April 19, 2020

Those fears are probably unfounded, understandable though they are. Film director Jason Hehir got a ton of Jordan’s uninterrupted modern time, meaning No. 23 had the platform to explain all his actions: the manic competitiveness, the sometimes cruel ways of needling teammates and opponents, the ego and the inner fire.

Even if the audience doesn’t always like what he says or what he did, chances are they’re going to marvel at the curtain being pulled back.

For a start, there is a lot going for Jordan and the show. There are no live sports to watch, so the love for nostalgia, especially that which deals with epic greatness and themed around an iconic figure, could scarcely be timelier.

Then there is the uniqueness. A young executive named Adam Silver was head of NBA Entertainment heading into what would be the final season of the Bulls dynasty in 1997-98 and was involved in the arduous task of persuading team ownership, Jordan and head coach Phil Jackson to let a film crew follow them for the season. It wasn’t the sort of thing that happened a lot back then.

I love to read these behind-the-scenes stories about how the sausage gets made. This piece about #TheLastDance doesn’t disappoint e.g. I had no idea current NBA commissioner Adam Silver was the head of NBA Entertainment at the time this doc was pitched. https://t.co/pMpwMzSqRG

— Evette Dionne (@freeblackgirl) April 19, 2020

And it is that behind-the-scenes access that makes the documentary what it is. During his career, what was largely seen of Jordan was national television broadcasts, a carefully protected endorsement-driven image and whatever nuggets a media led by local newspapers could glean from his increasing reticence to talk.

A lot that happened has never been known, the material having been buried in a vault for a nearly a quarter of a century, adding extra intrigue with each passing year. So no matter your generation as an NBA fan, Sunday will be the start of an unveiling of the true Michael Jordan — or the closest we’ll likely ever get, anyway.

For those of us who lived through the era of the Bulls, there is no two ways around it. It is going to make us feel old. Jordan and the Bulls were the biggest show and the biggest story in town, any town, anywhere. It was star power on steroids. It was big enough and vivid enough that it feels like yesterday, but, lamentably, it wasn’t.

It was way, way before social media. It was before camera phones, let alone those capable of shooting videos. It was before the spread of the internet, in the midst of a media world largely dictated by newspaper deadlines and available column inches. The year Jordan entered the league, in 1984, to be stunned by the drug-taking habits of his teammates on road trips, a baby called LeBron Raymone James was born in Akron.

When he broke through with that first championship, downing Magic Johnson and the Los Angeles Lakers in 1991, Kawhi Leonard was still three weeks away from appearing in his mother’s arms. By the time we get to the final season, the one with all the footage and the culmination of that shot over Bryon Russell, Zion Williamson, Ja Morant and Luka Doncic didn’t exist yet.

Michael Jordan’s NBA Playoffs Mixtape!

MJ went to the playoffs 13 times

Avg 30+ PTS in 12 of them

Scored 50+ PTS 8 times

Scored less than 15 PTS 0 times

Went to the Finals 6 times

Won a championship 6 times— Ballislife.com (@Ballislife) April 18, 2020

With those Bulls, historic brilliance was played out night after night, but things were chronicled differently back then. When Jordan did something spectacular, which was all the time, there were not the platforms available to instantly transport it to billions.

“If Jordan existed in today’s Twitter-mad, media-saturated world, the unstable internet would have already lost its collective mind,” wrote Sean Gregory in TIME.

And that means that even those of us who lived through the Jordan years, when “Mike Jordan” became “Michael Jordan” at Chapel Hill, or when he was known as a selfish scorer who couldn’t lift a team to a championship, or when he struggled to break through against a Pistons team that established rules just for him, only saw glimpses of the man. The good, the bad — it was all shadows on the wall.

No one likes a bully, and there is certainly that part of Jordan, but you can count on things being far more nuanced and layered than simple descriptors. Trying to become the best at anything is complex and laced with sacrifice. Nice guys don’t necessarily finish last, but the cream of the crop often have to let their nice side sit on the sidelines and make way for ruthlessness.

If America can warm to Joe Exotic, can they really hate the warts-and-all version of Michael Jordan?

Good things happen with 6 feet of social distancing. #StayHomeSaveLives #WeAreNotPlaying pic.twitter.com/KaFEHP6otf

— Chicago Bulls (@chicagobulls) April 18, 2020

“The Last Dance” will be a reminder for some, an education for others. Either way, it will help make Jordan real, both to a younger audience that knows him as a nigh-mythical figure and to those who became diehard NBA fans precisely because of his legend.

Some snippets have been leaked, and Jordan himself has done the rounds to drum up the promotion. It is clear he was invested in the project, so much so that he personally called former Presidents Obama and Clinton to secure their availability for interviews.

We are in a time in sports when no new history is being made, not the kind we want, anyway. But if you wish to watch sports, it is there – you have the entirety of filmed athletic history to call upon and to get to know in exquisite detail.

Arguably the finest athlete ever, and perhaps the greatest team, is a good place to start.